Recommendations For the BLM

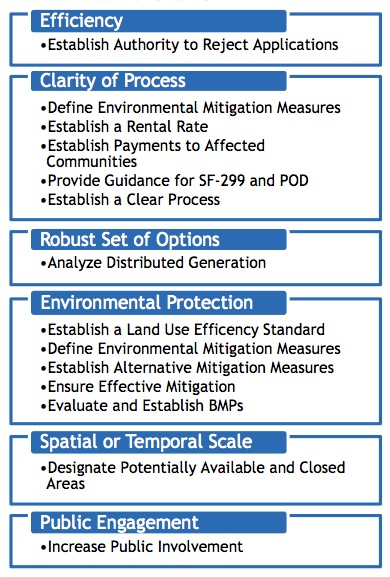

Based on our analyses of the environmental and visual impacts, socioeconomic impacts, and community attitudes regarding solar development, along with the analysis of the BLM Right-of-Way (ROW) process for solar and wind development and the oil and gas leasing process, we developed recommendations for improving the BLM process for evaluating solar development and siting individual solar facilities in the California desert (Table 1). These recommendations are meant to address concerns of potential environmental impacts, predicted

socioeconomic consequences, and deficiencies identified in our evaluation of the solar ROW process. Many of these recommendations are also based on the strengths of the wind ROW and oil and gas leasing processes. As the BLM evaluates solar development on its lands through the nationwide Solar PEIS, we recommend the following actions be taken and components be added to the evaluation of solar development and the permitting process.

- Analyze Distributed Generation vs. Utility-Scale Generation

- Designate Closed and Potentially Available Areas

- Establish Authority for BLM to Reject Applications

- Establish Efficiency Standards for Solar Technologies

- Define Effective Environmental Mitigation Measures

- Establish Alternatives to Acquisition-Based Mitigation

- Ensure Effective Mitigation

- Establish a Rental Rate Based on Installed Nameplate Capacity

- Establish Payments to Affected Local Communities

- Provide Guidance for SF-299 and POD Document Completion

- Increase Public Involvement

- Establish a Clear Process

- Evaluate and Establish Best Management Practices

1. Analyze Distributed Generation vs. Utility-Scale Generation

Determining how the nation will go about increasing production of energy from renewable sources is a major public policy decision. At the heart of this question is not simply the issue of siting utility-scale solar energy facilities, but also how the government should promote and incentivize solar energy production. While it may not be within the jurisdiction of the BLM, an agency of the federal government should conduct a comprehensive analysis comparing the energy production potential, land requirements, and environmental and socioeconomic impacts of distributed generation and utility-scale generation. In doing so, the government and the public will be better able to make critical decisions regarding how and if these types of solar generation facilities should be promoted. This recommendation does not apply to the BLM process for assessing individual facilities; however, it is important that this study be conducted before development begins. back

2. Designate Closed and Potentially Available Areas

The BLM should designate areas as either “potentially available” or “closed” to solar development, so as to eliminate any ambiguity about which areas are appropriate for solar facilities. Legally delineating geographic units as closed for solar development would enable the BLM to automatically eliminate applications for projects in these areas. An area designated as “potentially available” could be developed for solar energy; however the right to develop that land would not be automatic. Proposed projects must still undergo a full process evaluation to ensure suitability at the proposed site. Designating potentially available solar energy zones would give developers more certainty about areas to be studied for facility location proposals, though all site conflicts would not be eliminated by these area designations. For example, our analysis shows that SESAs could be designated as areas potentially available for development as they appear to have lower ecological and visual impacts.

For consistency across field offices, potentially available solar energy zone and closed area designations should be coordinated across the California Desert Conservation Area (CDCA) and would require amendments to all affected Resource Management Plans (RMPs). Any future changes to these designations would occur through the RMP amendment process.

In designating potentially available solar energy zones and closed areas, the BLM will likely have to justify each area’s designation. Potentially available solar energy zones should include those places with the least amount of known conflict and that are nearby to existing or planned transmission and other necessary infrastructure, such as roads. Closed areas should include all areas that are legally incompatible with utility-scale solar development, areas where a high conflict with existing uses or management designations is present, and other areas that are otherwise inappropriate for solar energy development. These closed areas would include, but not be limited to: Wilderness areas, Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs), Wild and Scenic Rivers, National Monuments, National Trails, Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACECs), Desert Wildlife Management Areas (DWMAs), critical habitat areas, special management areas including Mojave Ground Squirrel Conservation Areas and Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Management Areas, and areas containing significant cultural or historical resources. Other areas that may be appropriate for closure include Class L lands, Long-Term Visitor Areas (LTVAs), Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) open areas, and other areas of high- conflict as identified by the BLM field, district, or state office. back

3. Establish Authority for BLM to Reject Applications

The BLM should be given the ability to reject applications that are inappropriate due to land use conflicts, regardless of whether or not the recommendation to create potentially available and closed areas is adopted. The BLM should also be able to reject applications that remain incomplete even after the applicant has been notified and given the opportunity to correct any discrepancies. To make this rejection process transparent, standard criteria for rejecting an application should be developed and published. Criteria for rejecting applications should include failing to meet land and water use efficiency standards (Recommendation 4), failing to adhere to all published deadlines for application materials, and proposing facilities on critical habitat, ACEC, DWMA, special management area, or other incompatible area. The BLM should still notify applicants of application deficiencies and allow them 60 days to make changes to the Plan of Development (POD) and resubmit. With clearer application criteria, developers would have a better understanding of what standards their applications must meet, while still being encouraged to consult with the BLM to ensure any conflicts or information gaps are resolved as best as possible. back

4. Establish Efficiency Standards for Solar Technologies

The BLM should establish minimum land use and water use efficiency standards for all proposed solar projects in the Southwest U.S. Although environmental groups have concerns about inefficient technologies with large footprint sizes and water demand, the BLM has no authority to dictate types of solar technologies for proposed projects. By establishing these standards the BLM will have an additional criterion for rejecting applications. The Department of Energy (DOE), familiar with solar technology development and research, should develop this standard. The standards should be suitably high to effectively deny solar applications with technologies that are grossly inefficient.

Furthermore, efficiency standards will incentivize solar developers to propose more efficient technologies, such as dish/engine or power tower, and solar companies to develop more efficient solar technologies. Solar developers are currently incentivized to use parabolic trough technology because it is proven and investors are comfortable with proven technologies. However, our land use analysis showed that parabolic trough is one of the least land-use-efficient technologies with an average efficiency of 372 MW produced per acre disturbed. Meanwhile, dish/engine systems have a high land use efficiency with 923 MW produced per acre disturbed. Additionally, our water use analysis also showed that parabolic trough is one of the least water-use-efficient technologies with an average efficiency of 1,071 gallons of water consumed per MWh. Dish/engine systems appear to be highly efficient with four gallons of water consumed per MWh. The tools we developed for calculating the land use and water use efficiencies of a proposed solar energy facility, or their equivalent, should be used to calculate the efficiencies of each new project proposal once standards have been set. back

5. Define Effective Environmental Mitigation Measures

Mitigation is required for projects on public lands to offset development impacts to natural resources. Environmental, citizen, tribal, solar industry, and recreation groups have all raised concerns about yet to be determined mitigation standards for solar projects. It is necessary for the BLM to define these mitigation standards which guide whether a facility site can be suitably mitigated, how much private land must be acquired to compensate for impacts to particular species, and quality of mitigation land. Solar facility applications consistently state that BMPs and mitigation measures will render all ecological impacts of the facility “less than significant.” However, determining the amount of mitigation necessary to render impacts “less than significant” is difficult. The processes for determining the impact of the facility and the amount of land or money that would be necessary to reduce that impact is both subjective and expensive. The amount of land purchased or the amount of money set aside for mitigation is often negotiated among agency and developer representatives, and sometimes other interested stakeholders; as a result, these negotiations are often political in nature and not based on ecological knowledge.1 In the California desert, developers must currently fulfill mitigation requirements for impacts to special-status species, which includes the desert tortoise, western burrowing owl, Mohave ground squirrel, and flat-tailed horned lizard. However, these ratios are not standardized and are different across regulating agencies such as the BLM, California Department of Fish and Game (DFG), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Some examples from solar applications are:

- Desert tortoise mitigation ratios = 3:1, 1:1, and 0.5:1 (in acres).

- Western burrowing owl mitigation ratios = 6.5 to 19.5 : 1 (in acres) or 2:1 (in burrows).

- Mojave ground squirrel mitigation ratios = 2:1 and 0.5:1 (in acres)

Clear, standardized, and publicly available environmental mitigation ratios would allow developers to better predict future mitigation costs and allow BLM staff to establish a standard implementation and enforcement process for mitigation.

Additionally, while agency mitigation ratios can help guide land purchase decisions, they do not give adequate consideration of land quality. Whether it is even possible for mitigation measures to reduce the ecological impact of development to levels that are “less than significant” is addressed even less frequently. Therefore, the BLM should establish suitably high standards for the quality of mitigation land as well as define “less than significant” and evaluate whether each proposed facility site can successfully mitigate impacts to this level. Facility locations that can’t meet this mitigation level should not be given approval for development. back

6. Establish Alternatives to Acquisition-Based Mitigation

Given a likely shortage of suitable mitigation land, the BLM should establish alternatives as a complement to the traditional strategy of acquisition-based mitigation. Large solar facilities may require developers to acquire a substantial amount of mitigation land. One solar application determined that a total of about 215 acres would be needed to mitigate impacts to desert tortoise and Mohave ground squirrel. In another application, the developer determined that two-thirds of the mitigation requirement could be met by acquiring no less than 8,146 acres of land.

Considering that many utility-scale solar facilities could be sited in the California desert, and that many facilities will seek to acquire land for mitigation purposes, it is easy to imagine a shortage of suitable mitigation land. As Amy Fesnock, the Endangered and Threatened Species Lead for the California BLM, notes:

“When we’re the looking at the amount of projects currently proposed, there isn’t that much land with willing sellers to be purchased, and I think we have to begin to assess whether it is possible for us to actually mitigate the impacts of those projects on the land that we already have.”2

Suggested alternative mitigation strategies include funding research, restoration, agency staffing, and education. However, if a developer chooses to use one or more of these suggested alternative mitigation strategies, it is important that the specific use of funds must actually mitigate impacts by improving the status of sensitive species and habitats. back

7. Ensure Effective Mitigation

The BLM should ensure that any adopted alternative mitigation measures, including the above recommended measures or others, are effective. It is difficult to know how much research, restoration, additional staff, and education would be needed to adequately mitigate the impacts of a single solar facility, let alone the cumulative impacts of multiple solar facilities and associated infrastructure like roads and transmission lines. An independent economic analysis of the value of the resources at each individual facility is necessary to determine parameters for the proposed alternatives. If multiple facilities are to be developed, the economic analysis should consider cumulative impacts to be mitigated as well, especially from associated disturbances like roads. In addition, funds set aside for alternative mitigation must be used effectively. An assessment team or task force, partnering with the BLM, should define desired results, and evaluate and monitor the implementation and impact of alternative mitigation. Evaluation and monitoring should occur on a regular basis so that the effectiveness of these measures can be improved upon and the financial contribution of developers can be adjusted accordingly. back

8. Establish a Rental Rate Based on Installed Nameplate Capacity

Because solar energy is a natural resource that, similar to wind and oil and gas, will be extracted from federal lands, solar development should not use the standard ROW land rental fee. Instead, the BLM should assess an annual land rental fee based on total installed nameplate capacity. A rental fee should be assessed using the following formula:

Annual Rental Rate = (Anticipated total installed capacity in kilowatts on public land as identified in the approved POD) x (8760 hours per year) x (capacity factor) x (5.27 percent federal rate of return) x ($0.03 average price per kilowatt hour)

This rate is based on the current annual rental rate for wind development rights-of-way. The rental rate will be phased in with 25 percent of the total rental fee due the first year, 50 percent due the second year, 75 percent due the third year, and 100 percent due the fourth year and every year thereafter. The capacity factors that the calculation uses should be determined for each facility. back

9. Establish Payments to Affected Local Communities

Generally, solar development will have few negative socioeconomic impacts. However, California desert residents living in proximity to development will bear the brunt of these negative impacts. For example, it may be necessary for construction vehicles to pass through downtown areas to get to project sites, thereby increasing local traffic and dust emissions in these urban centers. Facilities may also affect the community’s viewshed, which may decrease the quality of life for nearby residents. Although communities near solar development will arguably be most affected, there is not currently a program for compensating these residents. The BLM should develop a funding program whereby a portion of facility rental payments is distributed among nearby communities to aid funding for public services. back

10. Provide Guidance for SF-299 and POD Document Completion

One major cause of delay in the project application process is incomplete SF-299 or POD documentation, which requires BLM staff to request missing information and to review documentation. To alleviate this problem, the BLM should provide clear guidance on the content and level of information needed in an SF-299 and POD. The Wind PEIS, which created a set of policies and best management practices and mandated what information was necessary in an application, may be used as a model. Developers would then know the extent of information and level of detail required, thereby placing the burden on them to file complete applications. Additionally, BLM staff would be able to determine the seriousness of an application based on whether the developer has followed the guidance. back

11. Increase Public Involvement

It is important to educate local residents regarding the proposed facilities. This provides the BLM and developer with feedback on local community concerns that should be incorporated into the project design or EIS. The stakeholder survey showed that desert residents are generally supportive of solar development, which is surprising given that many communities strongly oppose industrial development which would negatively impact their quality of life. This support may be the result of misconceptions regarding socioeconomic benefits, such as jobs and cheaper electricity, which are not likely to happen. Therefore, stakeholder outreach and involvement need to be better incorporated into the decision- making process.

However, based on the stakeholder survey, 74.5 percent of residents are unaware of opportunities to submit comments to the BLM on local concerns, 19 percent of residents are unable to attend a meeting due to inconvenient times, and 17 percent of residents are unable to attend meetings due to inconvenient locations. The BLM must increase public outreach and promote public involvement above and beyond the current minimum National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requirements. As the survey indicated, 85 percent of residents receive information from television and radio and 82 percent from newspapers. Therefore, the BLM should solicit public involvement through announcements in TV news media and local newspapers. Multiple public hearings should be held at different times of the day in communities within the vicinity of a proposed project, allowing residents with scheduling conflicts an opportunity to participate. back

12. Establish a Clear Process

Whether through the Solar PEIS process or independently, the BLM should establish an open process that is well defined and easily understood by BLM staff, developers, and interested stakeholders. The updated or newly established process will likely be refined as it is applied multiple times to process all applications, as is currently occurring with the solar ROW process. Despite knowing that the new process will likely not be perfect or please all stakeholders, standards can and should be developed to increase processing clarity and efficiency for both the BLM and developers. back

13. Evaluate and Establish Best Management Practices

Once permitted, solar developers will need to abide by several federal, state, and local environmental laws, ordinances, regulations, and standards (LORS). These LORS include the Endangered Species Act (ESA), Migratory Bird Treaty Act, Clean Water Act, and California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Biological Resources Best Management Practices, or BMPs, are on-site impact avoidance and/or minimization measures that are intended to reduce impacts to sensitive biological resources and aid in compliance with LORS. Currently, there is no formal guidance provided by the BLM on BMPs for solar developers. Therefore, some developers are proposing BMPs designed with general construction and facility operation impacts in mind. The BMPs being proposed need to be evaluated for effectiveness and the BLM should establish a standardized set of BMPs to provide clarity to developers and ensure minimal impacts to biological resources.

As an example, we sampled six solar facility applications and evaluated 35 of the proposed BMPs for their effectiveness in the context of the California desert. Our objective was to focus on the types of BMPs that are being considered, not to highlight individual projects. BMPs were not attributed to specific facilities, though some language from the applications is used here for the purpose of description. BMPs were placed into one of three categories: green (●), yellow (▲), or red (■). If a BMP received a green rating, it was considered to be an effective BMP (i.e., have a high likelihood of reducing ecological or biological impacts from development), with a low likelihood of unanticipated impacts and which the BLM should adopt. A yellow rating was given to BMPs that had potential to be effective, but had a medium likelihood of unanticipated impacts; the BLM needs to improve such BMPs or needs more information or clarification to evaluate it. A red rating was given to BMPs with a high likelihood of unanticipated impacts and/or ineffective reduction of ecological or biological impacts. The BLM should not adopt BMPs which received a red rating and should require developers to use an alternative BMP.

BMPs and ratings are presented here. BMPs with yellow and red ratings have comments attached which explain why that rating was given as well as suggestions for alternatives. We also commented on BMPs that were given green ratings and could be useful to all solar facilities, but were only found in few applications. Overall, areas where proposed BMPs should be improved by the BLM include:

- Preventing or reducing the establishment and spread of invasive plants in disturbed areas.

- Preventing or reducing indirect mortality of desert tortoise and other wildlife.

- Monitoring the effectiveness of BMPs and allowing for adjustment if inadequate or ineffective.

1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Staff Member 2, Personal Communication, August 3, 2009.

2 Amy Fesnock, Endangered and Threatened Species Lead, Bureau of Land Management, Personal Communication, December 8, 2009.