Viral Marketing Overview

From The Yaffe Center

(→II. The Buzz Campaign Process) |

m (Viral Marketing moved to Viral Marketing Overview) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions not shown.) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | == Acknowledgements == | ||

| + | |||

| + | A large portion of this Wiki was taken from the research paper “Buzz in Practice” by Joseph Ferencz and Stephen Hellerman; students at Ross School of Business. | ||

| + | |||

== I. Introduction == | == I. Introduction == | ||

| Line 4: | Line 8: | ||

The purpose of this paper is to provide marketers with an understanding of the intellectual underpinnings of Buzz marketing and a strategic and tactical framework for harnessing the power of Buzz marketing. Through the structured approach described in this paper, marketers will gain the ability launch and manage a Buzz marketing campaign in a way that will optimize ROI, however that goal may be defined. The tactics in this paper are also tools that a marketer can use to manage a spontaneously occurring Buzz campaign/naturally occurring brand buzz to generate incremental ROI from ongoing traditional campaigns. | The purpose of this paper is to provide marketers with an understanding of the intellectual underpinnings of Buzz marketing and a strategic and tactical framework for harnessing the power of Buzz marketing. Through the structured approach described in this paper, marketers will gain the ability launch and manage a Buzz marketing campaign in a way that will optimize ROI, however that goal may be defined. The tactics in this paper are also tools that a marketer can use to manage a spontaneously occurring Buzz campaign/naturally occurring brand buzz to generate incremental ROI from ongoing traditional campaigns. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

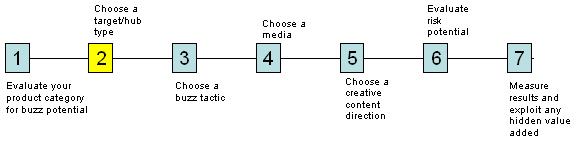

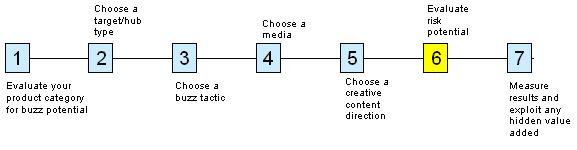

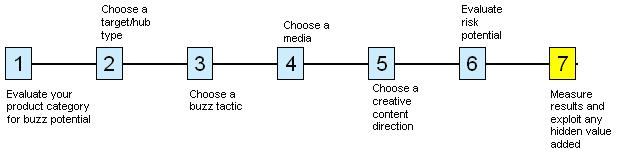

== II. The Buzz Campaign Process == | == II. The Buzz Campaign Process == | ||

| + | |||

| Line 161: | Line 163: | ||

[[Image:Buzz 18.jpg]] | [[Image:Buzz 18.jpg]] | ||

| - | + | ''' 6. Evaluate Risk Potential: The Five Risks of Buzz Marketing''' | |

[[Image:Buzz 19.jpg]] | [[Image:Buzz 19.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz marketing can offer great rewards to marketers. When consumers or the media spread a brand’s message it is cheaper and more effective than when the brand’s marketers do it all on their own. But, there are significant risks: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Brand Risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because much of today’s buzz marketing leverages the connectivity of the internet, and because the demographics of moderate and heavy users of the internet skew younger than the population overall, marketers often feel the impulse to be “edgy” online, that is, run more provocative content than they would in more traditional media. Levi’s, usually a paragon of American values and relatively safe advertising, engaged in an outrageous viral email campaign called “Unbutton Your Beast”, which showed various monsters emerging from the zipper of men’s jeans with different spoken messages. It generated a lot of publicity, but almost all of it was negative. People either thought it was crude and unimaginative or just downright offensive. Levi’s is a mass-market brand that cannot afford to alienate any of its target market. The company would have been very unlikely to run this campaign as a television ad, but in order to generate buzz and viral pass-alongs, it clearly felt it needed to be more provocative. Marketers must weigh the value of viral and WOM effects generated by edgy content against any damage to brand equity or reputation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Misinterpretation Risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz campaigns often shoot for a level of content sophistication that surpasses traditional advertising. This is necessary to give consumers the social currency to spread the buzz. But, when a campaign becomes too sophisticated, it may confuse either/both its target and other consumers to whom it is exposed, leading to negative consequences for the brand and the company. The Cartoon Network attempted to launch a buzz campaign to support Aqua Teen Hunger Force, a late night, cult cartoon program by placing neon representations of the show’s characters around major metro areas in random locations. In Boston, some local residents thought that the neon character representations were bombs and called the police, leading to a major and costly response from local authorities. Cartoon Network ended up eating the cost of the campaign, which had to be pulled from every city in which it was launched, as well as a $1MM donation to the city of Boston to cover expenses and damages incurred by the false bomb scare. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Counterproductive Buzz Risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sometimes when buzz spreads from either too pervasively within one network, or to one network too many or too far afield, some consumers may lose interest or turn off to the buzz and/or product. A Stanford study showed the effects of counterproductive buzz using Lance Armstrong’s ubiquitous “Live Strong” yellow bracelets. First the researchers distributed the bracelets through one dorm on Stanford’s campus. The bracelets were popular and the buzz created through their easy to spot nature and the intriguing story behind them led to many sales to students in that dorm. Then the researchers distributed the bracelets within a second dorm, one with a reputation for being less socially prestigious. As the bracelets were adopted by the second dorm’s residents, students in the first dorm lost interest in wearing the product. 32% of those who were wearing the product in the first dorm stopped, thereby reducing the buzz opportunities for the product. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Deception Backlash Risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many marketers believe that in order for consumers to pass buzz along, the consumers must be unaware that they are disseminating an explicitly commercial message. In fact, consumers appreciate honesty and do not see a stigma to explicitly branded buzz marketing efforts. Nonetheless, marketers will doubtless continue to try and market under the radar. When consumer inevitably find out that they were unwittingly used by marketers, there can be a backlash that can hurt brand equity and even sales. Sony Ericson ran a campaign in which actors approached consumers on the streets of major cities and asked them to take a picture with a Sony Ericson camera. The actors then exposited on the merits of the camera; the whole time the consumers engaged thought they were dealing with friendly strangers. When word leaked that the friendly strangers were in fact hired actors, there was major backlash. Consumers were outraged that Sony Ericson duped them, and the story went all the way up to 60 Minutes, where it served as an emblem of brand marketing run amok. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Poor ROI Risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though a standard methodology for measuring buzz marketing ROI still eludes marketers, there is certainly a risk of wasting money on buzz campaigns. Brad Harrington, president of the Cutwater Agency, an advertising and branding firm, estimates that the chance of a viral campaign succeeding is only 10%. | ||

| + | |||

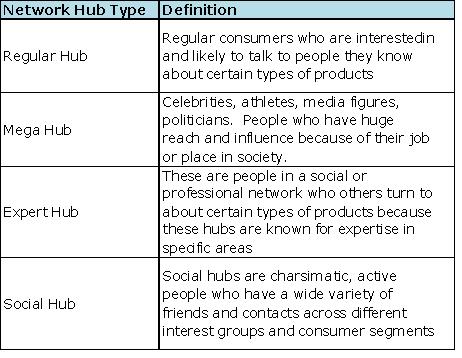

| + | '''7. Measure ROI and Exploit Any Hidden Value Added''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Buzz 20.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | A marketer must be able to draw accountability from any channel used. Buzz marketing is no exception to this rule. However, measuring ROI for a buzz marketing campaign is currently a difficult endeavor for many reasons. It is important for anyone with a desire to utilize buzz marketing to understand some of the pitfalls and challenges associated with measuring buzz marketing ROI, the measurement methodologies currently being utilized, and ways to improve ROI measurability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Problems with measuring ROI | ||

| + | |||

| + | Determining how to measure ROI is a large challenge facing any company deciding to utilize buzz marketing. The following charts show some of the metrics that marketers were using as of 2006: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Buzz 21.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Further attesting to the lack of standardized ROI metrics, in a survey of 114 buzz campaigns conducted for this paper, metrics varied from unique visitors to a website to sales conversions in a direct-sales situation. Because of the lack of a standard metric such as GRPs in television or click-through in online display advertising, advertisers and agencies take liberties with deciding how they will measure and report results. The broad range of evidence cited as proof of efficacy for buzz campaigns in the survey seemed indicative of a pervasive positive deviation bias in reporting results. In general, to create a measurement system with integrity, it is probably best to decide on a metric at the outset rather than at the conclusion of a campaign. The next few pages will continue to discuss why choosing a proper metric is so challenging and what current best practices are for measuring and optimizing ROI on buzz campaigns. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz Marketing is still in an emergent state | ||

| + | |||

| + | As with any new form of advertising, best practices for metrics have not been established. | ||

| + | The ideal metric buzz marketers would like to see would be one that links the campaign directly to incremental sales. However, this lofty goal has often eluded even more established forms of advertising. Although work is being performed in this area by certain organizations, such as BzzAgent’s collaboration with the Wharton School of Publishing, nothing definitive has yet emerged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So, although being able to measure incremental sales from a campaign might lie at the end of the road, there are other results from a campaign that are measurable, in fact, there is no shortage of metrics available. Metrics utilized include straight statistical items such unique visits and product mentions to (the increasingly common) interpreted metrics by paid firms including such items as “How consumers feel about you in their own words” “Brand Sentiment”, and NetPromoter score. With such a diverse range of metrics available, the question becomes which of them are relevant to a given campaign. Although it might seem like relevant metrics should flow easily from the campaign goal (e.g. driving traffic to a site should monitor incremental traffic flow), there also exists the question to what degree should other metrics play in judging the effectiveness of a campaign? For example, should a campaign designed to increase brand awareness judge effectiveness solely on mentions or should incremental unique visits to the site be taken into account when measuring success? | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition to the question of how to measure there also exists the question of what to measure. Should a company limit itself only to immediate campaign results or should it attempt to understand the impact the campaign has on its longer-term reputation? This question of scope is another that has not been fully explored in academic or professional circles, and the lack of true consensus adds to the difficulty in measuring the ROI of buzz marketing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Different products may require different use of metrics | ||

| + | |||

| + | The nature of a product also effects ease measuring the effectiveness of a buzz campaign. A product purchased more frequently may show trends that are more easily attributed to a given campaign. But for goods with longer sales cycles, such as heavy-duty household appliances, cars, and high-end electronics, the measurements become much more complex as the effects are manifested over a much longer period of time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, products with longer sales cycles will use different metrics to judge the effectiveness of a campaign. Where a short sales cycle product might draw a correlation from the campaign to incremental sales, those with longer sales cycles might examine metrics such as customer satisfaction and brand awareness. The proper point in time at which a company should use long-term versus short-term type metrics for products using buzz marketing has also not been fully explored and this ambiguity adds further complexity to properly measuring ROI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | WOM occurs largely offline | ||

| + | |||

| + | Word of Mouth is a large part of any buzz marketing campaign. WOM help to enable a campaign to be buzz, rather than decaying, in nature. In a recent interview, Malcolm Faulds, VP of Media Services stated that offline interaction makes up 80-90% of word of mouth. Most of the tools for tracking word of mouth involve harvesting data from online mediums from blogs to social networks. It is impractical for a company to properly track all of the offline mediums by which WOM can be translated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Current methods used | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Despite all of the difficulties mentioned, there is no shortage of tools (paid and free) and companies available for use in tracking the results of a buzz marketing campaign. The trend in analytics seeks to move from purely monitoring online sources of information keyword recurrence to developing a concrete framework for evaluating a buzz marketing campaign’s ability to drive sales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some of the popular tools are Google’s Insights for Search, Google Analytics, AWStats, Webalizer and W3Perl. Google Insights for Search measures the frequency of a keyword relative to search volume across certain segments (e.g. region, city, language). Google Analytics gives users statistics about users of a website this includes conversion rates, uniqueness of visitor, and referrer site. AWStats, Webalizer, and W3Perl offer the more tech savvy ways by which traffic can be monitored and broken down into individual reports. However, these last three don’t offer an easy preconfigured means by which data can be segregated on relevance to measuring a campaign’s effectiveness. In addition they are server centric and thus cannot measure the effect of a campaign as might be exhibited on any external site. As such these tools are of less use then some of the paid for tools from companies such as Nielsen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Paid tools and accompanying analysis services from companies can get extraordinarily sophisticated. Top tracking tools include Buzzlogic, Radian6, and Nielsen’s Buzzmetrics. Buzzmetrics is a top example of what is offered in paid tracking services. A short list of Nielsen’s Buzzmetrics includes (in addition to standard keyword tracking) such diverse elements as identification of target audience, where they go, and what they do online, measurement of streaming media and online video consumption, examination of web audiences by site, demographic profile and behavior. These products deliver this information usually in near real time and with a polished graphical interface. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Companies such as Nielsen also offer services such as helping you to understand specific issues that are being discussed around your company, brand organization, how your online and offline marketing campaigns resonate with consumers, and how to leverage word-of-mouth to drive brand credibility. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the tools are highly sophisticated and the trend is towards developing a means of directly evaluating buzz marketing campaign’s ROI, none of the above mentioned tools seems to have achieved either dominance over the others or industry wide acceptance as a standard. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A final point about automated analytics is that automated systems, no matter how sophisticated still can get the measurements wrong. When analyzing these numbers, a human making decisions based on experience is necessary. Is a mention of a keyword being used sarcastically? Or perhaps the keyword mention is part of proving something unrelated to either the brand or campaign? Do the trends make sense, if not, why? These are questions that an automated system might not pick up, and hence the value of the human element cannot be understated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | How to design a campaign for maximum ROI measurability | ||

| + | |||

| + | When designing a campaign, there are a few steps that can increase a campaign’s ROI measurability. These include enabling consumer feedback, choosing a unique etymology for a product, utilizing first part rather than third party cookies, and exhibiting transparency in what data is collected and its use. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Enable consumer feedback | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are a variety of consumer feedback collection methodologies available to a campaign. This includes standard methods such as customer satisfaction surveys and creating forums for users to talk either with each other or representatives behind the buzz marketing campaign. By initiating and ongoing dialogue with the consumer a marketer can gain valuable insights into the effects of a campaign. These insights can be used not only to learn about the consumer and product for future campaigns, but also to adjust your current campaign for maximum effectiveness. A marketer should constantly poll consumers for feedback. Actively evaluate positive and negative feedback. For example, marketer’s for Chevrolet’s “make your own ad” campaign learned just as much from anti-SUV campaigns uploaded by entrants. Also, include methods of dealing with negative feedback in any plan for a WOM campaign. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Utilize unique etymology for a product | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most tools and companies use mining for keywords as a portion of their methodology. By utilizing a unique name for the product or campaign, a marketer can increase the accuracy of these search tools. For example, a tool searching for a keyword (or keyword combination) will be able to more accurately identify the mention of a campaign with a unique name like “Quencherator” than a campaign using ubiquitous terms such as “Gatorade Thirst Quench”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | First party rather than third party cookies | ||

| + | |||

| + | Companies that wish to track the information and statistics of visitors to their sites often make use of tracking cookies. In many instances these have been issued by a third-party vendor. However, the disadvantage of these cookies to consumers is that it allows tracking across websites other than the original site at which it was issued. With increasing technical savvy, users have begun to block these third party cookies. By utilizing first party cookies, that is cookies issued by the original site’s subdomain, there is an increased likelihood that a user will neither block nor delete a cookie, especially if it is from a trusted source. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Transparency in data collected and its use | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even when utilizing first party cookies, there is still the distinct possibility that a user will indiscriminately delete a cookie. If a campaign offers the consumer information on how the data collection will be used it will increase their experience as a consumer, then they will have another reason not to delete that cookie. A large loss of accuracy for web analytics happens when cookies are blocked or deleted. An increase in the amount of cookies enabled will result in an increase in accuracy and amount of analytics collected. This will in turn better enable more accurate means of measuring ROI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Serendipity and Hidden Value | ||

| + | |||

| + | While buzz marketers continue to advance their craft through refining best practices and ongoing research, some of the best buzz campaigns of all time were born of rather conventional marketing strategies and tactics. This paper refers to inadvertent buzz as serendipity because marketers see a significantly higher ROI/lower CPM than was budgeted when buzz occurs spontaneously. For example, Apple’s famous 1984 advertisement ran as a one time television advertisement, meant to catch people’s attention and position Apple as an innovator against a stodgy IBM. Because the commercial was so original though, consumers wanted to watch it again and again. Apple’s decision not to buy more air time for the commercial, made the commercial newsworthy, and Apple benefited from millions of dollars in free media placement. The lessons for marketers is that buzz can result from a variety of strategies and tactics, not just from explicit efforts towards generating buzz. Being aware of when a more traditional campaign may have organically transitioned in a buzz campaign will allow a marketer to maximize the opportunity and hopefully guide the buzz discourse. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz marketing also has hidden value in its ability to deliver valuable consumer insights to marketers. The Crocs brand of molded rubber footwear monitors the blogosphere in order to understand how to improve existing products and design new ones. The buzz marketing agency BzzAgent has seen numerous occasions when their WOM agents find something unique in the product that the marketers had not noticed. One notable example involved a new brand of sausages that had hired BzzAgent to promote the product through WOM. The manufacturer directed BzzAgents to talk about the sausage’s low fat content, but the WOM agents actually discovered that the sausages were extremely non-greasy, and that this was a very appealing product characteristic. They focused their WOM discussions on the non-greasy aspect of the sausages. Listening to a product’s buzz can direct marketers to what characteristics of a product consumers value most, and tailor future marketing efforts to highlight those characteristics. When a buzz marketing campaign provides valuable information on how to optimize future marketing efforts, it is delivering additional value to the marketers, value that was hidden during the design of the campaign. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Based on the understanding that a campaign can serendipitously deliver value when consumers buzz about it, and that even a buzz campaign can deliver hidden value by delivering unexpected insights and information, marketers can make sure to reap these rewards by facilitating and monitoring their marketing efforts. Facilitation means helping those who are exposed to any marketing campaign spread the message if they so choose. For example, a magazine ad can have an online component that is easily disseminated or not. If a consumer sees a hypothetical magazine ad and wants to share it for an idiosyncratic reason and there is no online component, it will be much more challenging to share. Creating a digital copy that can easily be passed along is a way that a marketer can facilitate serendipitous buzz. Similarly, if consumers are buzzing about a certain characteristic of a given product other, then by monitoring the situation a marketer can leverage that insight in future communications, thereby extracting hidden value from the initial buzz. Monitoring can take the form of asking for feedback at the point of transaction online, starting a forum, or any other way that marketers can listen to unfiltered consumer feedback on a campaign or product in real time. Facilitation and monitoring are not mutually exclusive. They are inextricably intertwined and the more monitoring a marketer does, the easier it will be to facilitate buzz. Likewise, the more a marketer engages in facilitation, the more there will be to monitor! | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Ferencz and Hellerman: Our Thoughts on Buzz Marketing | ||

| + | |||

| + | We embarked on this paper with a layman’s knowledge and no strong opinions on the topic of buzz marketing. As marketers, past and future, we wanted to develop a thorough and objective understanding of buzz marketing, by combining the best of academic and industry research, and conducting some new research of our own. Our goal was to create a playbook of sorts, something that marketers can use to plan buzz campaigns. And, we hope that our seven-step process has demystified the process and created a finite set of considerations for that purpose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the writing of this paper, we’ve realized that both proponents and detractors buzz marketing often have vested concerns in seeing marketers increase or decrease their buzz marketing budgets at the expense of other forms of marketing. Through reading numerous books, hundreds of articles, and reviewing a vast array of websites, youtube videos, and blogs, we’d like to think that we’ve gained a certain knowledge of buzz marketing. This knowledge is free from the agendas one might find from proponents and detractors. We’d like to share a few of our own unbiased observations and intuitions about buzz marketing: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why is your brand buzz-worthy? | ||

| + | |||

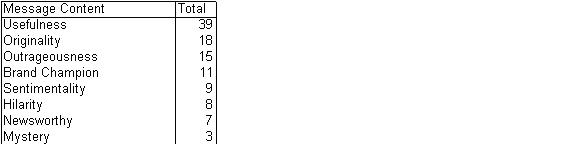

| + | The question of buzz-worthiness should guide your buzz campaign planning process. Note that 35% of all campaigns we surveyed used usefulness as the main message content. It’s significant that Usefulness was so often utilized because most of the campaigns we examined were considered successful by the companies responsible for them. (While a few spectacular failures are well documented, it is very challenging to find information on buzz marketing that simply didn’t fulfill expectations.) If your brand fills a market need, then intuitively there should be some natural route to generating buzz. If your brand does not fill a market need, then why does your brand exist at all anyway? We understand that not every brand truly solves a market pain, especially in CPG or fashion, where the market pain may be an unrealized psychological need, or in entertainment, in which any given product is inherently superfluous at its introduction. In that case, you need to be a little craftier, and that’s when you can look to your existing brand personality or product features to guide your buzz marketing efforts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The best marketers and advertisers in the world have been successful at creating a “story” for brands. The best example of consistent success in this regard may be renowned ad agency Crispin Porter Bogusky, who starts of every strategy session for a new client by asking “How are we going to make this brand famous?” One of the agency’s most notable successes in finding a story is the Microsoft “I’m a PC” campaign. Most would have considered Microsoft to be fairly devoid of buzz potential given its ubiquity (not to mention the brand’s pre-existing frenemy status with consumers). The campaign though, as of March 2009, had inspired over 45,000 consumers to submit pictures and videos declaring themselves PCs as well. The story that Crispin created for Microsoft was that consumers were tired of being painted as boring and unfun by Apple for owning PCs. The campaign tapped into a vein of indignant pride that Microsoft’s very buzzworthy competitor had in fact seeded in its own attempt to create buzz! If Microsoft can find a story, we’re sure that almost any brand can. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Don’t abandon your brand when you buzz! | ||

| + | |||

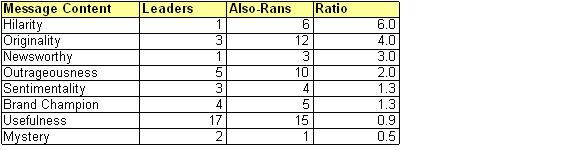

| + | Use buzz marketing as a synergistic tool in your marketing campaigns, not as an end unto itself. The biggest offenders in this regard are viral videos. However, this trend is also prevalent with various web schemes that are not video. The relative youth and mercurial nature of the web encourages marketers to go wild! Some marketers believe consumers won’t be interested unless they’re more original, more outrageous, more risqué, etc. Our research shows this belief is not only incorrect, it is harmful. Campaigns that used “Outrageousness” as the main content message, straying from the original brand message (such as Levi’s Unbutton Your Beast), have been known to actually hurt brand image and equity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Buzz 22.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

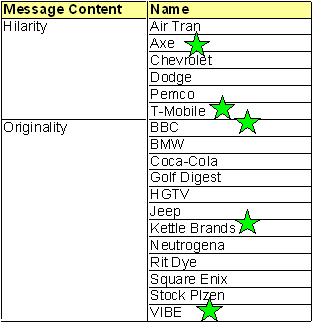

| + | Consider the above table, which shows how often, in a survey of 112 buzz campaigns, industry Also-rans used various message content types compared to Leaders. Most notable, Also-rans were relying heavily on hilarity and originality (meaning novel message content, not novel product features). It is doubtful that these brands had hilarious or original product features or brand equity, meaning there may have been an incongruity between brand and message. In fact, we’ve examined the brands that could conceivably claim either Hilarity or Originality as a product feature or aspect of their brand equity. But, we’ll let you decide for yourself. Below are the Also-rans who used Hilarity and Originality in campaigns that we surveyed: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Buzz 23.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | With the exception of Axe and T-Mobile, who are known for their humorous commercials, and BBC and Vibe, who must necessarily be known for originality as they are content generating firms, and Kettle who was promoting an original flavor, all the other brands were well outside their product feature and brand equity comfort zone. Marketers should ask themselves, why do consumers already like my brand? Or, in the case of a non-established or transitioning brand, why should consumers like my brand? Let that help guide buzz marketing efforts as it will help create synergy with your other campaigns in the market, and leverage your existing brand equity. It will also avoid potential damage to overall marketing ROI by confusing and off-putting consumers. Based on this logic a brand like Coca-Cola should be messaging with sentimentality. Golf Digest should promote its usefulness or use a brand champion to increase its credibility as a source of useful information. Historically, Coca-Cola does message with sentimentality and Golf Digest utilizes usefulness and brand champions. But, for some reason, when planning a buzz campaign, they abandoned their core brand message. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz cannot be forced, but it can be tapped | ||

| + | |||

| + | One thing that has become clear in our research is that consumers want to be involved in marketing brands that they like! BzzAgent and P&G’s Tremor agency understand this fact and have leveraged this consumer interest in being amateur marketers to great effect. BzzAgent is the most remarkable: it has found a way to get its consumer “agents” to hype brands of which they weren’t previously aware and products that they had never before used, within their networks. The secret? Ask them nicely and give them some information and a sample! P&G’s Tremor has an installed base of stakeholders, as its original “army of moms” was highly invested in finding the best household products. By giving its constituents samples, Tremor allows consumers to engage in one of their favorite activities: gaining and spending social currency. Humans are social creatures, and they buzz first and foremost for that purpose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With this in mind, marketers should find their natural brand ambassadors and empower them to spread the word. Most CPG marketers don’t think of sending a free case of product to their brand’s heaviest, most loyal users. The question for them is, “Why would you give away product to people who would otherwise have paid full price?” This logic is similar to asking “Why would you get your wife a Valentine’s Day gift: she’s married to you anyway?” Marketers are in a relationship with their brand’s consumers, and the more goodwill engendered, the more it is reciprocated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because of the desire consumers have to be involved with brands, we believe that Brand Champion-based message content may be under-utilized. A “Brand Champion”, a consumer who can credibly promote your brand and create buzz, was only used in 10% of buzz campaigns that we surveyed. We believe that there is significant room for growth in this messaging technique. And, because of the inherent credibility of information from within one’s network, Brand Champions likely offer the most efficient route to accomplishing any given business goal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On a related note, one trend in tapping buzz we did not see was entertainment firms making use of Brand Champions. While entertainment companies are generally on the cutting edge of buzz marketing, and certainly make excellent use of events, web technologies and the blogosphere to create buzz, there is a great opportunity for use of Brand Champions, especially to drive box office receipts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Experiment with buzz marketing to meet many business strategies | ||

| + | |||

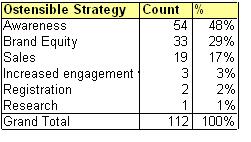

| + | Marketers want to get consumers talking about their brands. But what about buying their brands? What about getting low cost market research, or lead generation? When looking at our survey of Buzz marketing campaigns, it is awareness and brand equity, the two most ROI nebulous of goals, predominate. Intuitively, because of the measurement problem of buzz marketing, it makes sense that marketers choose to focus on goals that are hard to quantify and measure, but we believe that this is shortsighted. There are a variety of tactics and messaging strategies that can drive sales, both at retail and e-tail, and assist with other information capture goals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Buzz 24.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | One major element that many buzz marketing campaigns are missing is a call to action. Marketers seem to be afraid that branding a buzz campaign too conspicuously might turn consumers off. However, consumers hate being misled (e.g. Sony Cameras) and furthermore want to be involved with brands that are relevant to their lives. So, if you’re designing a contest, or a viral web promotion, create a sales promotion to accompany it. Tastefully incorporated, it’s hard to imagine a sales promotion upsetting consumers to any significant degree. A good deal might even help the buzz spread! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most of all, listen to your consumer and have fun! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz is a two-way communication. That is, at its essence, the difference between buzz marketing and traditional marketing. You speak to the consumer, and the consumer speaks back, maybe circuitously through how they interpret the campaign, but speak back they do. Listen to them. It will help guide not only your buzz campaigns, but your traditional campaigns as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In marketing, we like things to be measurable. Marketers need to show the finance guys the ROI on our efforts. We understand that, but, guess what, good luck figuring out how many people are talking about your brand to their friends after entering your contest or viewing your viral website! We can measure some things, like links and email impressions, but some things may not ever be measurable. And, we think that’s OK. In fact, it’s better than OK. It’s quite right. When you engage in buzz marketing, you’re personalizing the brand, you’re setting your brand free in the land of human beings, and to expect to be able to measure the effort exactly is like expecting to measure how many times you mention that last episode of Lost to your friends and co-workers. You don’t want to measure that! It would suck all the fun out of talking about it. Similarly, when you start a buzz campaign, turn it over to the consumers, let them have fun with it, and have fun with them. Because when everybody’s having fun with your brand, they’re going to want to keep spending time with it, and that probably means they’re going to keep spending money on it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Appendix: Buzz survey methodology | ||

| + | |||

| + | While conducting research for this paper we closely read over 80 articles, as well as 5 books relating to Buzz marketing. We decided to collect as much data as possible from these resources. Our goal was to find data that could provide us with some prescriptive uses of Buzz marketing and also which strategies, tactics and executions were generally the most successful. Complicating this goal, though, was the fact that there is no standard metric by which to judge a campaign’s success, and many of the campaigns we studied were either in the planning or execution phases, so there were no results to analyze at all! | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the end, in our initial secondary research we came across 23 campaigns that had a beginning middle and an end. But, that was too small a sample, especially given the broad number of variables against which we hoped to collect data. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To supplement our sample we turned to the Word of Mouth Marketing Association (WOMMA), which is a trade organization that helps track and promote non-traditional marketing efforts. On their website, broken down into 28 subcategories, are over 100 buzz campaigns. For each of these campaigns we tracked the industry, the marketer’s relative market position, the main and primary tactic used, the execution strategy, and whether or not the company considered the campaign to have met its goals. Most of the campaigns we surveyed from WOMMA are self-described successes, which makes intuitive sense, since few companies would want to post the results of a failed campaign for the world to see. Therefore, one could look to our survey to find what could tacitly be described as de facto best practices, although clearly this is not a scientific sample. Future research in Buzz marketing could work towards creating a more balanced sample and more conclusive results could then be drawn. But, as it is, our survey provided us with some interesting insights into how companies that are interested in being known for their Buzz marketing attempts are approaching the discipline. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Minicases: == | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Minicase 1: Food Product''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Introduction'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bree Sarta, Brand Manager of Coba, looked again at the information regarding consumer data on her desk. The facts were in: Coba’s consumers spent more time on the internet than any other media outlet. And Coba had set in motion marketing efforts to make use of this fact. Until this time, Coba had spent little time developing campaigns that utilized the internet as a medium. Given the small budget available for advertising in non-traditional mediums, any campaign would have to somehow combine being effective yet also relatively inexpensive. Bree needed to find the best way to accomplish this. She had bet that a buzz campaign could offer the solution to solve these seemingly incongruous goals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nutritional Food Market | ||

| + | |||

| + | Approximately eight million people in the US don’t eat meat and need to find ways to get protein into their diet. Three percent of the US adult population is vegetarian according to the Vegetarian Resource Group. About half of these are vegans, those who adopt a stricter regimen, choosing not to partake in any animal products. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Within this space, Coba competes with several soy-based products that could satisfy both vegetarians and the stricter vegans. The largest competitors in the arena were Amy’s and MorningStar Farms, who both offered an equally diverse range of products. In addition to MorningStar and Coba, there were numerous other brands, many of which were owned by larger food and beverage companies. Other specialty retail stores, such as Whole Foods, produced private-label soy-based products in order to compete. Food industry observers predict that ongoing growth in this category will be driven by an aging US population that increasingly wants healthy alternatives in their diet. There also seems to be a growing interest in vegetarianism among teenagers, particularly girls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Coba Brand | ||

| + | |||

| + | Coba brand focused in meatless, soy-based, products, including meatless alternatives to burgers, chicken, and other entrees such as chili. It had built an image as a health and wellness kind of brand. Although small in size compared to some of its competitors, such as Amy’s or MorningStar, the category had been growing, creating opportunities for capturing new customers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Previously, Coba used print as a key vehicle to reach its customers. It also used some limited digital for its PR. Recently there had been movements within PR in general to use digital and specifically viral methods to generate buzz around Coba. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Coba Consumer: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The marketing research revealed some interesting facts about the Coba user. The typical Coba consumer is about 35 – 54, educated, with a good income. She uses the internet and is constantly seeking info on what is healthy and seeks to make fact-based decisions. Also, she is very picky about what she is buying: she wants the best product. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With this consumer in mind, the next step that Coba pursued was to determine her media habits. Further research revealed that the savvy consumers of Coba were always seeking information: namely nutritional information about products. The internet was the media used by the target consumer to find this information. The most typical sites visited were various food blogs. The decision of if to become involved in the internet with Coba became a question of how to use the internet to best reach their information hungry consumers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cost Effective Viral Through Blogging | ||

| + | |||

| + | The decision to pursue a viral strategy through bloggers came from learning about their consumer and her habits. Coba had decided to go with a balanced message for buzz creation (using its traditional print media as well). As the consumer is always seeking information, Coba sought to provide it to them. To this purpose, Coba researched many of the top food blog spots such as “edible notes with beth and joe”. Within these sites, Coba discovered individuals within their target consumer profile who combined a seeming receptivity to Coba brands with a prolific output into the blog space. They dubbed these individuals “key influencers”. Coba started testing the waters, first with a single key influencer, and then with more (with ever differing profiles within the target demographic.) If they received a favorable response from the blogger they could move forward and share more about Coba. From this, Coba hoped that the buzz would become significant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next Week | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next week Bree had to make a decision on the best methodology for further promoting Coba Brand. Should they increase the amount of bloggers used? If so, should they further explore the food blogoshpere of should they expand in other directions? In addition to execution concerns, there were other questions, how should they measure the success of their efforts? Although the agencies had offered several types of metrics, Bree felt that measuring the effectiveness of bloggers was not as easy as simply measuring unique impressions to their blogs. Also, given the mercurial nature of media, wellness trends, and social media, was blogging her best option? What would be the best way of dealing with the control that was given up by using independent bloggers to promote their product? | ||

| + | |||

| + | All of these thoughts raced through her head as she went through the information before her for the seventh time. The optimal solution was there, and she would find it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Coba Buzz Marketing Campaign | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using the Seven-Step Process for Building a Buzz Campaign, Bree executed her campaign as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1) Identify the type of product. Coba is a product with high compatibility for its target consumers; people seeking to make healthy, informed decisions would choose Coba brands. This campaign would need strong, impact-full information to make an impression on target consumers. | ||

| + | 2) Target a hub type and locate the target. Given the previously described consumer, namely one seeking to make informed choices about a more niche type of product, Bree felt that a regular hub was the best choice for a network hub type. By choosing those hubs already established within the nutritional food arena, Coba could convert these bloggers who were interested in and likely to talk about Coba brand. | ||

| + | 3) Choose a buzz tactic. In this case, Bree decide to give users social currency to talk about Coba brands. Coba interfaced with select individuals among the food blog sites to disseminate knowledge about the Coba brands. They encouraged these consumers to parse branded message content through idiosyncratic buzz channels. | ||

| + | 4) Choose a media. Coba brand took a multi-media approach. It utilized the resources of its parent food and beverage company to use traditional media, mainly print, to build PR. It used the Web/Mobile media, spread the word through blogs, and enrolled brand ambassadors, giving them economic currency in the form of free products so that they could become more familiar with brand attributes. | ||

| + | 5) Choose a creative execution. The Coba message would include usefulness as its main component. The attributes of the Coba products would be disseminated to key influencers within the food blog space. The primary thing was that she talks about her POV. Somehow within this she should be able to incorporate Coba. | ||

| + | 6) Evaluate risk potential. A major part of the Coba strategy for building buzz through the blogosphere was for key influencers to talk about their POV and somehow incorporate Coba brands into that. By first discovering individuals who appreciated the Coba brand’s attributes, Coba had limited brand risk. The largest risk was an ROI risk: the chance that various members of the blogoshpere would ignore key influencers and fail to generate buzz. | ||

| + | 7) Measure ROI and assess hidden value added. Bree planned to assess ROI by surveying members of the nutritional foods blogosphere. She would determine what impressions they had garnered from their key influencers: are they talking about Coba, how interactive are they with each other, are they talking about their experience? Most importantly, what are the mentions about Coba brand, and how does that measure against the competition. There was also the possibility of garnering some hidden value as the discussions of Coba brand might include valuable feedback on both product attributes and consumer needs. This information would help in planning the next generation of Coba products. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Minicase 2: Female Personal Care''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Introduction | ||

| + | |||

| + | Josephina Kim stared at the pro forma P&L on her screen. She was still learning the ropes as a brand manager at PersHygienics, Inc., how to best utilize TV, print and web advertising to push that market share needle a few points higher. But, now she was in a new situation that called for a new approach: Launching a niche women’s personal care product, FemGenie, with a fraction of the budget allocated to more established brands. She had been hearing a lot about “buzz marketing” in the trade press as a way to generate ROIs that were much higher than traditional media, but had no experience planning and managing buzz marketing campaigns. After doing some web research, she was thinking of starting a contest, maybe enlisting some “brand ambassadors”, starting a myspace page for her product, or even commissioning a viral video. She was due to present her marketing campaign to the VP of her division in a week and time was running out. Was Buzz markting the way to go? And if so, how should she approach it? | ||

| + | |||

| + | PersHygienics, Inc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | PersHygienics, Inc. was a well-established company in personal care and hygiene products. Its product range included a variety of women’s personal care products, as well as some cosmetic products, such as hairspray and shampoo. It had distribution at every major retail player, although it was small company compared to giants like P&G and Unilever. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The company’s strategy was to profit from the white space opportunities that were too small for P&G or Unilever to fully address, and the company pursued a mostly premium product strategy. PersHygienics tended to look for very specific market segments in the form of demographics or psychographics, and then pursue those segments with strongly tailored product development and marketing. Therefore, most of the company’s product lines had fairly high customer loyalty, especially in a market where price was often a deciding factor. The company was a leader in internet marketing because niche the internet is the most efficient media for niche targeting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | FemGenie | ||

| + | |||

| + | The FemGenie brand was being marketed as a fun, fashionable women’s personal care product. Its target market was women aged 18-34 who lived in and around America’s biggest, most fashion forward cities. The positioning statement was, “Everything in your life is stylish, shouldn’t your personal care products be as well?” | ||

| + | |||

| + | In focus groups, consumers had responded very positively to the concept and price point. So, the launch strategy was to create awareness and stimulate trial. But, because it was positioned as a premium item, mass giveaways to stimulate trial were deemed unlikely to generate the WTP necessary to achieve profitability going forward. Josephina needed to figure out a way to get people to try the product, but without explicitly giving it away for free. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Traditional Media Campaign Possibility | ||

| + | |||

| + | Josephina was considering a traditional media campaign. The campaign would focus online, with some print as well. Josephina had requested rate cards from a few celebrity and fashion blogs. The CPMs for those sites were reasonable, but she felt intuitively that consumers reading about Jennifer Aniston’s latest hook-up might not wish to click on an ad for personal care products. Also, those sites all wanted to charge for impressions, not clicks, and Josephina knew that display advertising for an experience product might not generate the desired results. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Buzz Marketing Campaign | ||

| + | |||

| + | The more Josephina thought about it, the more a buzz marketing campaign made sense. Still, she couldn’t decide how to implement it. Furthermore, she was unsure about she would sell the idea to her VP, since there had been little done before and tracking ROI was going to be a challenge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using the Seven-Step Process for Building a Buzz Campaign | ||

| + | |||

| + | 8) Identify the type of product. FemGenie is a product that provokes an emotional reaction. Unfortunately, it is a somewhat taboo topic for polite conversation. This campaign would need a strong message and execution to achieve success. | ||

| + | 9) Target a hub type and locate the target. Josephina thought that brand aspiratioal women who liked to trade fashion tips would be the best hubs. These represented a hybrid of expert and regular hubs. She would target them by buying creating marketing partnerships with fashion blogs, sites, and perhaps some print publications as well. | ||

| + | 10) Choose a buzz tactic. In this case, Josephina decided to create a contest to encourage people to visit the site and spread the site, and encouraging consumers to parse branded message content through idiosyncratic buzz channels. | ||

| + | 11) Choose a media. The FemGenie brand took a multi-media approach. It built a website to host the contest that used email to drive traffic, spread the word through blogs, and enrolled brand ambassadors, giving them economic currency in the form of free product to give away at their discretion. | ||

| + | 12) Choose a creative execution. The FemGenie message would include mystery and originality. The designs on the personal care products would be kept secret, with a new one revealed each month for the first six months. The originality would be played out by the brand ambassadors, who would blog, email, and spread WOM about this novel new product. | ||

| + | 13) Evaluate risk potential. Josephina saw very little risk for this strategy. The biggest risk was that by putting it out into the blogosphere and engaging brand ambassadors, that some women might reject the concept outright, and without strong advertising to counteract that bad WOM, the line could be relegated to the dustbin of history. | ||

| + | 14) Measure ROI and assess hidden value added. Josephina planned to assess ROI as accurately as possible by using surveys to see who was reached and how, and then calculate the ROI from there. In terms of hidden value she thought that perhaps they would get valuable feedback on the designs the products would carry and maybe even new ideas from enterprising consumers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Presentation | ||

| + | |||

| + | Walking into her VP’s office to present her planned campaign, Josephina was nervous, but excited. Her calculations showed that her buzz campaign would generate significantly higher ROI and sales than if she spent he same money on traditional media buying and messaging opportunities. But, she was in unproven territory. Only time would tell if her planning had paid off. | ||

Current revision

Contents |

[edit] Acknowledgements

A large portion of this Wiki was taken from the research paper “Buzz in Practice” by Joseph Ferencz and Stephen Hellerman; students at Ross School of Business.

[edit] I. Introduction

Traditional marketing, such as a television ad showcasing a laundry detergent’s relative cleaning power, is a linear marketing strategy, the goal of which is grab a consumer’s attention for long enough to deliver a scripted message. Buzz marketing represents a divergent marketing strategy; its goal is to leverage the impressions created by an initial marketing message by inciting consumers to organically spread that message or an interpretation of that message through the consumer’s social or professional network. Buzz marketing can serve a wide variety of products and be implemented in countless ways. The one thing that all Buzz campaigns have in common is that they get consumers and media outlets to spread the message for free. Outside of that, Buzz, if properly executed, can serve any product or service. Some campaigns use the internet to allow consumers to spread information or participate in games or contests, other campaigns attempt to get the mainstream media to pick up a story or piece of content and spread it to consumers, who will then talk about it with each other, still other campaigns offer free products to consumers in the hope that they will then tell their friends about it. Pick any media where information can be transferred, any product category, and any genre of marketing content, from purely functional to purely entertaining with no over commercial message at all, and Buzz marketers have attempted to find a winning combination of those factors to accomplish their business goals.

The purpose of this paper is to provide marketers with an understanding of the intellectual underpinnings of Buzz marketing and a strategic and tactical framework for harnessing the power of Buzz marketing. Through the structured approach described in this paper, marketers will gain the ability launch and manage a Buzz marketing campaign in a way that will optimize ROI, however that goal may be defined. The tactics in this paper are also tools that a marketer can use to manage a spontaneously occurring Buzz campaign/naturally occurring brand buzz to generate incremental ROI from ongoing traditional campaigns.

[edit] II. The Buzz Campaign Process

Ability and Desire

At its most conceptual level, creating a buzz marketing campaign is about giving consumers both the ability (often through connective technologies) and the desire (in the form of social or economic currency ) to buzz about your product or service. Of course, in theory, every consumer has the ability to buzz to someone about anything they want to. In that respect, ability and desire are not distinct entities, but symbiotic components, and lack of desire can be compensated for by enabling the ability to buzz, and vice versa.

In today’s cyber-connected world, the ability to buzz has grown tremendously, as the cost of sharing information has fallen to nearly zero, there can be little doubt of that. While twenty years ago, if one wanted to share a newspaper article with a friend, one would have to cut it out and either fax it or mail it. A significant time investment, and some financial investment, was necessary either way. Today, someone with a few mouse clicks and keystrokes can accomplish that same thing.

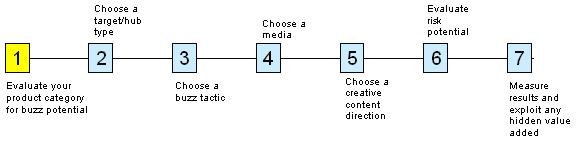

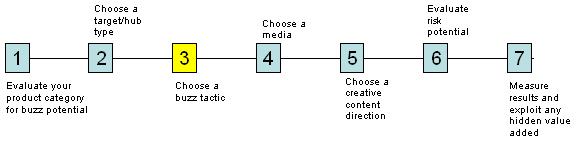

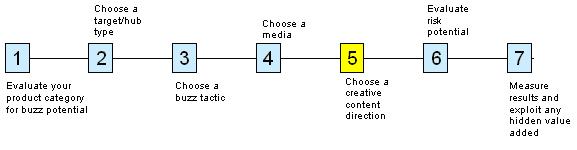

Beginning with understanding how likely consumer are to buzz about your product, one can plan to create the optimal amount of desire, matching with the appropriate facilitating technologies, to inspire consumers to buzz. Below please find the 7 step process this paper has identified for designing a successful buzz campaign. The remainder of this section will proceed through the Buzz Campaign Process in a step-by-step fashion.

1. Evaluate Your Product Category for Buzz Potential: Different Product Categories Have Different Inherent Buzz Proclivity

Naturally, consumers will talk about certain classes of products. Entertainment such as music and movies, are frequently discussed commercial products. Products that are highly personal and potentially embarrassing, such as some personal hygiene products, do not come up often between friends and co-workers. Essentially, the question is, does my product or service inherently give consumers the desire to buzz? Understanding the answer to that question will guide the next steps of the process.

Exhibit 3.6 lists the product classifications that are inherently likely to generate buzz, and some examples of the types of products that fall in each classification.

Increasing the Your Product’s Buzz Factor

As a marketer, sometimes one is charged with creating buzz for what is an inherently dubious buzz proposition. If that’s the case, the problem can often be reduced to product positioning and buzz facilitation. In accordance with the theory that ability and desire to buzz drive successfully buzz campaigns, a marketer must find the group with the most stake in buzzing about his product, and then give members of that group the ability to buzz. For example, a beautifully designed car like a Ferrari might “evoke an emotional response” in almost any consumer. But, a less obviously emotionally evocative product, like an online search tool, can also produce an emotional response based purely on marketing. Google chose a very distinctive, playful name and used public relations to highlight its corporate mission of “Do No Evil”. Certainly, Google did “increase efficiency” and was buzzworthy for that, but many other search engines provide arguably comparable quality of results. It’s playful and distinctive name likely sped mass adoption by increasing awareness and recall and its corporate mantra of “Do No Evil” created an “emotional response” that aided in gaining press and securing user retention. When designing a buzz campaign, a marketer can evaluate the intrinsic qualities of the product, but should also create external features through marketing, branding and PR that increase buzz potential. Those external features can be directly linked to the product’s functionality, which can increase intrinsic buzz factors, or can be a complete invention to compensate for a lack of intrinsic buzz factors.

The next few sections of the paper contain the main strategic guidelines for building a successful buzz campaign, regardless of how innately buzz-worthy a product may be.

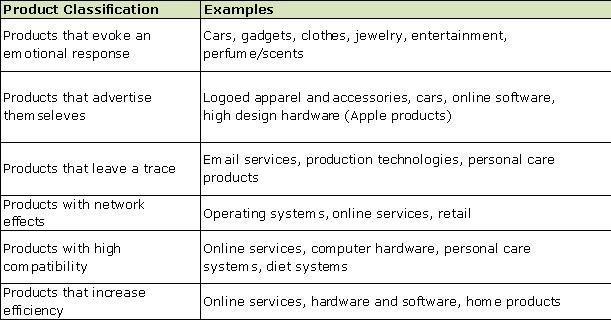

2. Choose a Target/Hub Type: Targeting a Buzz Campaign for Maximum Effect

Not all consumers are created equal from a buzz perspective. Intuitively, those consumers who are shy, or who simply do not know many people, are unlikely to be a valuable conduit of a buzz campaign. Those consumers who have large networks, enjoy sharing information, and who are also considered a credible source of information within their networks, are the most likely to spread buzz.

Most every buzz marketing agency and marketing research outfit has its own proprietary name for these elusive consumers who have large networks. They can be referred to as connectors, magic people, influencers, etc. This paper finds that “network hub”, or just hub for short, is the easiest and most accurate shorthand for consumers who have large professional and/or social networks, enjoy disseminating information through one or a variety of media, and have credibility.

The process of choosing a target/hub type is effectively the act of identifying which consumers will have the highest desire to buzz about your product or service. If one was planning a campaign for a drug that cures a common, deadly disease, one need not worry too much about identifying the correct networks and network hubs to spread the word. But, for most products, buzz will spread within networks that are in the pre-existing product market domain, and it is network hubs who innately have the desire to spread buzz in general, and will spread the buzz about your product or service if they like the message.

Anatomy of Buzz, by Emanuel Rosen, is considered by many in the marketing field to be the most complete treatise written on the consumer psychology and behavior that fuels product and brand buzz. The book breaks down these network hubs into four main categorizations. Exhibit 3.4 lists the four types of network hubs and the definition of each.

Regular Hubs are the most common and there is some knowledge about Regular Hubs that marketers can use to find/identify them: Regular Hubs tend to be travelers, information hungry, vocal, media consuming, and early adopters. This profile of Regular Hubs is not surprising. All of the activities listed are ones that produce social currency, or conversational topics. Therefore, the more active a consumer is, the more likely he will want to share tales of his activities with his network!

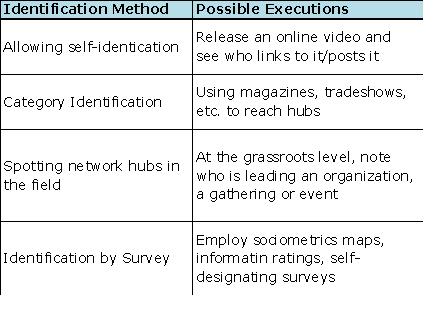

Anatomy of Buzz also identified four ways for marketers to identify network hubs. Exhibit 3.5 lists the methods and possible executions for each method.

The Alternative Theory of Network Hubs

While there can be little doubt as to the value of network hubs for disseminating information, recent evidence shows that ability and desire to disseminate information throughout a network is more common that previously thought. This alternative theory of networks hubs essentially posits that more consumers than not fall into the category of Regular Hubs, and that a plurality of Regular Hubs is more likely to spread buzz than a small number of Mega, Expert, or Social Hubs.

The Alternative Theory of Network Hubs states: (CITATION NEEDED)

The internet has allowed people to spread information to people quickly and easily. The "moderately connected majority" rather than the much smaller number of super connectors have the greatest potential to deliver WOM information. The more people that one is connected to, the more likely a person is to spread knowledge throughout their network, and therefore sheer connectivity is the best predictor for buzz potential.

This theory has major implications for marketing through online social networks.

Connectors: Linking Disparate Networks

Anatomy of Buzz also documents the phenomena of “connectors”, those individuals who serve as the vital link between two otherwise disparate networks. Information can become trapped in network clusters, therefore finding the connectors is an important part of making sure that buzz reaches the maximum number of interested parties in the fastest and most cost efficient manner. For example, students often have time to research and experiment with new technologies. Thus, to create usage of a new technology like Google Docs, an online suite of office products that allows multiple parties to edit documents simultaneously, Google might spread buzz through campus channels. But, many professionals can also use this service, though they may be harder to reach and to induce trial usage because of the opportunity cost of their time, leading to a more difficult and expensive campaign. In this case, students who are about to graduate are connectors between student networks and professional networks because they can take the buzz they heard as students to a new network when they join the professional workplace.

Connectors can be identified by their group affiliations (many), because information circulates within groups, and travel habits (often and widely), because information spreads geographically. In the internet age, it is easier than ever to identify a connector. While a hub might be someone on Facebook who has many friends or posts frequent status updates, a connector will also have membership in numerous interest and professional groups.

3. Choose a Buzz Tactic

While media is where the buzz campaign takes originates, the tactic is how a marketer gives a consumer the ability to buzz. For example, a website can simply give a visitor product information, purchasing information and contact for the company. A site like that would not be utilizing buzz marketing techniques. But, as soon as the website contains a button that can email the URL of the site to any email address that the visitor inputs, the site becomes part of a buzz campaign. Actually successfully incentivizing a visitor to use that pass-along technology is highly dependent on the nature of the message, which this paper will cover in the next section. Again, the greater the desire of the consumer to share a given piece of information, the lower the level of facilitation the sponsor need provide. This section concerns itself simply with options that a buzz marketer offers to consumers or the press in order to help the product message spread.

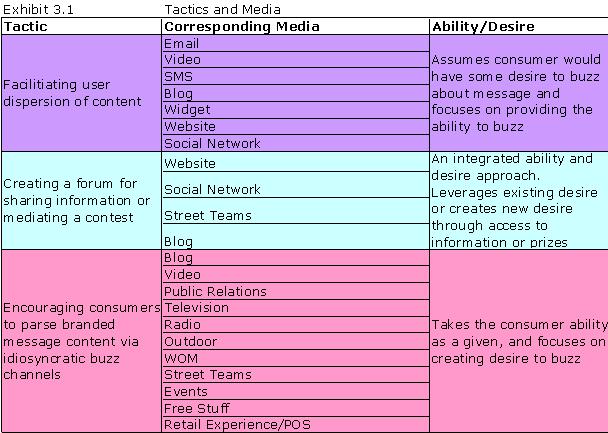

After conducting a survey of over 100 buzz campaigns, three high level tactics emerged, each with various media and content considerations. It would be erroneous to assume that there are clear boundary lines between each of these tactics. The best campaigns often cross over into all three during the campaign’s lifetime. But, most campaigns are launched with one of these specific tactics in mind as the primary tactic. Exhibit 3.1 shows the three main tactics and which media correspond to each. Campaigns that illustrate these tactics are described in the proceeding pages.

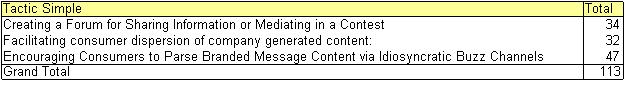

The survey further revealed the breakdown in tactics thusly:

Clearly, although the broadest category in terms of execution possibilities (Encouraging Consumers to Parse Branded Message Content…) is the largest, the other two tactics are well represented. One can infer from this distribution that, of the companies self-reporting ostensibly successful buzz campaigns, best practices in terms of tactics have yet to emerge. Overall, though, the lack of a dominant tactic speaks to the idea that different tactics can serve very different marketing goals for different brands. As a marketer, one must analyze the goals of the campaign and identity of the brand to decide which tactic is best suited to be the primary driver of a buzz campaign.

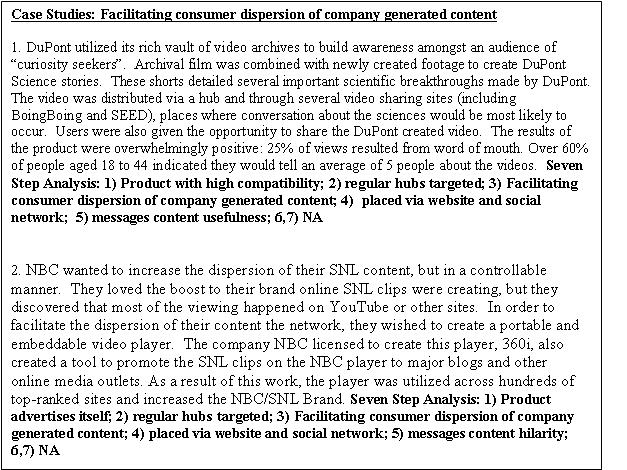

Buzz Tactic 1: Facilitating consumer dispersion of company generated content:

Facilitating user involvement in dispersion of content is a distinct tactic in that it attempts to carefully guide how consumers or press will parse the marketing message to others in their networks. Facilitating user involvement in the dispersion of content is in fact the basis of a number of high profile web businesses today, such as Digg.com, which allows users to mark articles and other web information for pass-along to other dinn.com users. News articles, other editorial and entertainment are naturally things that consumers and the press want to disseminate within their networks. For a marketer, the challenge is how to incentivize people to pass along a message that may not be inherently interesting to consumers.

This tactic allows marketers to maintain greater control over the messaging than tactics that encourage consumers to reinterpret information or create their own content for dispersion.

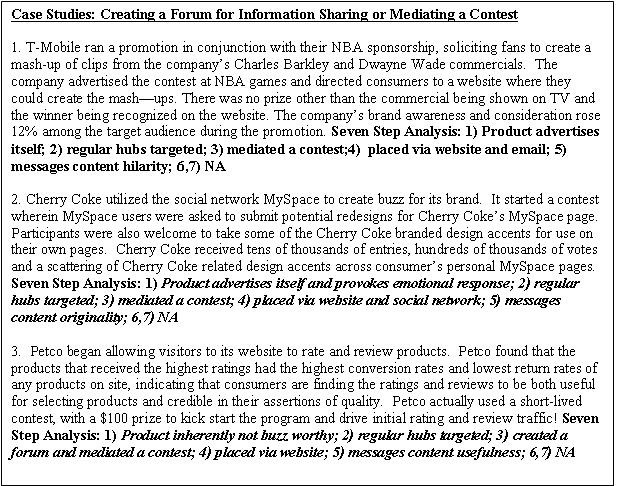

Buzz Tactic 2: Creating a Forum for Sharing Information or Mediating in a Contest

Creating a Forum for Sharing Information or Participating in a Contest takes the opposite approach from Facilitating Consumer Dispersion of Company Generated Content by aggregating all target consumers in one place in order to serve them with messaging, rather than attempting to have consumers string the message across their networks. This tactic still allows marketers some control, but less than in facilitating content dispersion because consumers will be either generating some kind of content in order to enter the contest or be sharing their thoughts and knowledge through the forum. This tactic intrinsically offers consumers more value than simple content dispersion because they will either be competing for something through the contest or accessing valuable information through the forum. Sometimes, the forum and the contest are one and the same! An example of a combination forum and contest might occur in a recipe contest, where all recipes entered are posted to a central website, but only the winning recipe receives a prize. As in the recipe contest/forum example, a contest or forum may have an explicit prize, such as cash or a merchandise, or an implicit prize such as recognition and some measure of fame or notoriety from the publicity of winning. The table on the next page chronicles a few prominent examples of this tactic and shows how those campaigns fit into this paper’s Seven Step Process.

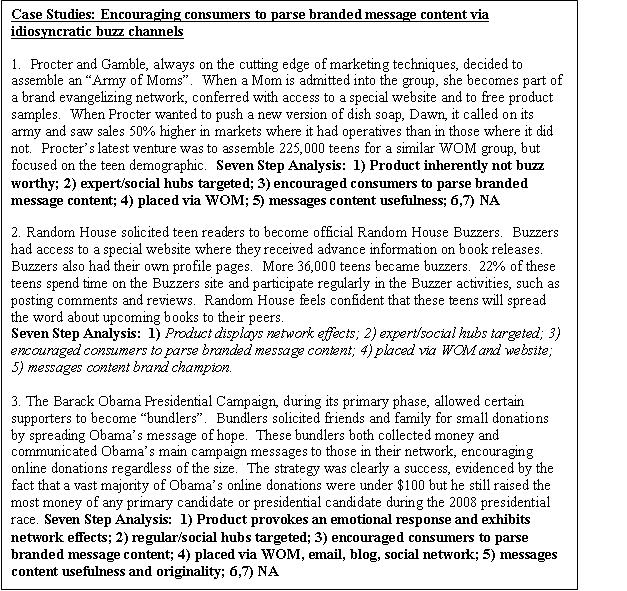

Buzz Tactic 3: Encouraging consumers to parse branded message content via idiosyncratic buzz channels

This tactic is both the riskiest and most potentially rewarding in terms of generating true buzz and WOM amongst consumers. Encouraging consumers to parse branded content can mean a variety of things, but this tactic assumes that consumers will have the desire to spread the message content they are presented with. The most commonly spread messages contain unique/scarce information and special privileges/titles. Another way to create desire amongst consumers to buzz is by giving them economic currency of some kind. Economic currency, in the context of marketing, usually takes the form of free merchandise. BzzAgent, a well regarded, Boston based WOM marketing firm, has seemingly mastered the art of giving consumers both social and economic currency. It allows consumers to self-select to be BzzAgents, thereby conferring upon them the special honor of being a BzzAgent, that is, someone who knows the inside information on upcoming products and what makes them special. Because being a BzzAgent is generally a long-term commitment, the agency is providing these consumers with both the special title and the inside information! But, when possible, BzzAgents actually receive product samples on which to base their talking points, that is, an economic incentive to talk about the product. Events, street teams, and retail experiences are all excellent ways to give consumers some social capital for conversation. Anything that is unique, that a consumer will find memorable and interesting to a friend or colleague, is social capital.

The BzzAgent Agency has created a very efficient pipeline for starting buzz campaigns. So, why doesn’t every brand in the world jump on board? Because marketers tend to be risk averse. Although marketers can control the message and the swag, they cannot control how consumers react to it. BzzAgent itself cannot make any guarantees on how it’s army of influencers will relate the products benefits, or lack thereof, to their respective social and professional networks.

One thing that marketers should know before engaging in this tactic is that most brand conversations still occur as live conversations rather than online. While surely it’s easier for consumers to disseminate a marketer’s actual content online, the same consumers are less likely to actually engage in a discussion about the content online. Therefore when marketers aim to create WOM buzz, they should literally aim to create WOM buzz and imagine how two consumers might discuss the product of messaging in a live context and how that will influence purchase behavior.

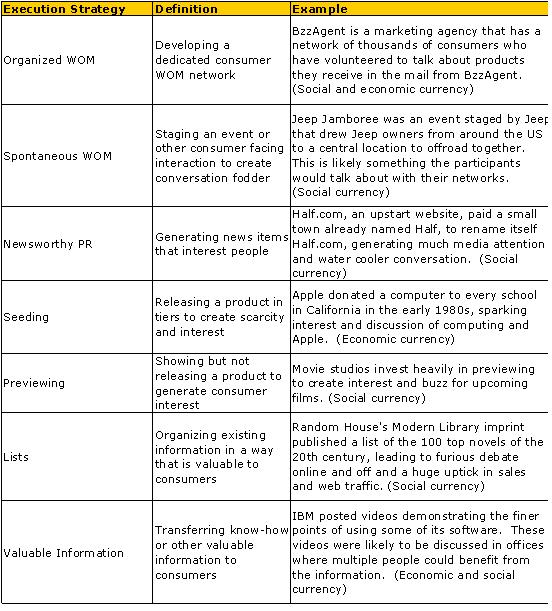

Buzz Tactic 3a: Seven Strategies for Encouraging Consumers to Parse Branded Message Content specifically through WOM

Many marketers may be laboring under the misbegotten notion that in order to create strong WOM amongst consumers, they must engage in a specific WOM campaign. In fact, research shows that general advertising, especially television and online, (JAR - Missing Link p. 430,431) can stimulate both online and offline WOM.

Research for this paper has identified seven execution strategies for creating an effective WOM campaign. Exhibit 3.2 provides the names, descriptions and examples of each. A cagey reader might realize that some of these same execution strategies reappear as types of creative content that is likely to spark buzz. But, the categories in exhibit 3.2 are distinct from the message content in that these are specific executions for a WOM campaign, as in giving consumers economic or social currency, while the creative content categories can apply to any of the three main tactics discussed in this paper. Later in this paper the high-level execution strategies, that apply to all three Buzz marketing tactics and that can generate consumer buzz, are cataloged in detail.

Exhibit 3.2 Different Execution Strategies for Encouraging Consumers to Parse Branded Message Content specifically via WOM

4. Choose a Media

Buzz marketing campaigns can be executed across any media, or in the case of WOM, across no actual media at all. Since the rise of Youtube, online video has undoubtedly been a popular media for marketers to employ in the hope of “going viral”. In fact, according to eMarketer, 72% of the clients of US advertising agencies expressed that they were either “interested” or “very interested” in viral video in 2008. In general, web media such as online video, blogs, email campaigns, social networking plays, and widgets have dominated the efforts of Buzz marketers for the past few years. Surely, the way in which the web connects consumers to each other makes any web media a great tool for implementing WOM and viral campaigns. But, evidence suggests that traditional media can still be very effective in generating buzz amongst consumers.

Broadly, Buzz media can be broken down into Traditional Media, Web/Mobile Media, and Off the Map Media. Exhibit 2.2 documents the specific media channels in each of the aforementioned media types.

Exhibit 2.2

There has been some industry and academic research into the effectiveness of various media in regards to creating positive WOM amongst consumers. Advertisements online and on television are the most likely mediums to spark WOM among consumers. Retail POS advertising was found to be about half as effective as television in generating WOM to consumers. Print advertising is the least likely to get consumers talking about the product or message. The existing research suggests that marketing itself is a powerful driver of positive WOM amongst consumers. Anecdotally, it seems that today’s marketers often prefer to operate in stealth mode when engaging in buzz marketing. They appear afraid that branding a “viral video” might discredit the video and discourage pass-alongs. Research, though, suggests the contrary. Research from the Keller Fay firm indicates that 50% of conversations about brand include mention of some official media or marketing communication from the brand. And, far from being dead, television can still be a major conversation starter, the Super Bowl and Oscars being the best examples of television advertisements creating buzz. When placing an ad in the Super Bowl, it’s almost a sure thing that the ad will generate some significant buzz, even if it’s just people critiquing it with friends while it airs during the game.

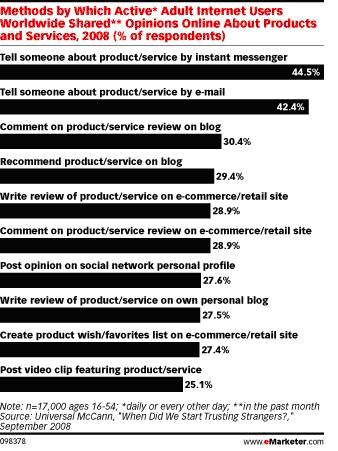

Universal McCann has research that digs deeper into how brand positive buzz spreads online. Universal McCann’s research, exhibit 2.4, indicates that IM and email are the most common methods by which internet users age 16-54 share opinions about a product. In all of the research conducted for this paper, not one instance of marketers actively engaging in an IM campaign was found. IM campaigns could be an area of opportunity for buzz marketers operating under increasingly intense competition for share of consumers’ minds/mouths.

Another noteworthy result was that the least common for internet users to share an opinion was by posting a video clip featuring a product/service. While viral video tends to be an inexpensive way to ostensibly reach many consumers, Universal McCann’s research indicates that it does not serve as a way for consumers to relate product information to each other. Might this be because so many viral videos focus exclusively on entertainment at the expense of any meaningful product/service information? See the “Buzz Editorial” section of the paper for a deeper discussion of the pros and cons of viral video, and more broadly entertaining at the expense of informing.

5. Choose a Creative Content Direction

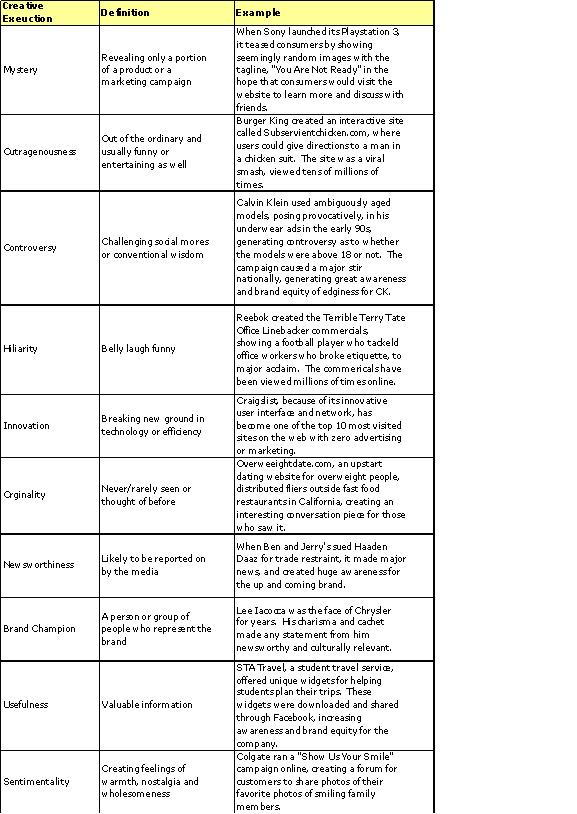

Once a marketer has decided what medium and what buzz tactic to engage in, the next question is how to guide the creative for creating optimal consumer desire to buzz. This paper has aggregated academic and trade research on how to design creative content for buzz campaigns. There are ten broad categories of creative content into which all successful buzz campaigns fall. Exhibit 3.3 lists each creative content type, its definition and an example. These executions can be applied to any of the three main buzz tactics and in any media.