Grazing and Agriculture

The 1980 California Desert Conservation Area (CDCA) Plan states that: “Currently and historically, livestock grazing has been and continues to be a significant use of renewable resources on public land in the California desert.”1 Under the CDCA Plan, the BLM leases 4.5 million acres (36 percent of public lands in the CDCA) to graze cattle and sheep. While livestock production provides benefits in the form of food and fiber, there are negative ecological impacts. Negative impacts of livestock grazing in desert ecosystems include decreased plant cover and biomass, changes to the vegetation community, soil disturbance, soil compaction, and more variable distribution of water and soil nutrients.2 Overgrazing may trigger the decline of arid rangeland through a positive feedback cycle of damage to vegetation and soil structure, reduced capacity of the soil to capture and retain water, leading to slowed recovery of vegetation (Figure 1).3 Livestock can also damage soil crusts, which has serious implications for desert ecosystems. The impact that livestock has on soil structure and plants may negatively affect wildlife that depend on desert vegetation for shelter or food.

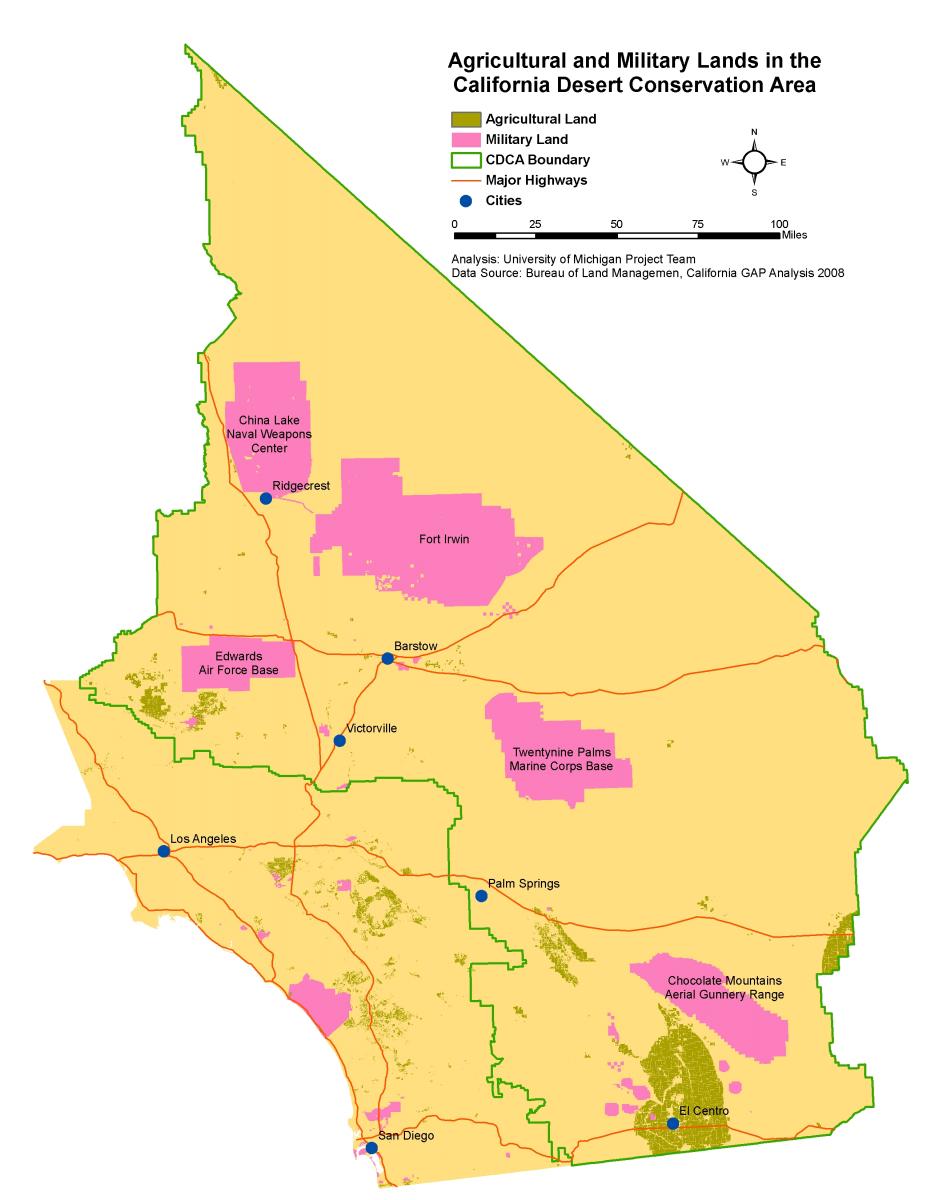

Agriculture occupies several hundred thousand acres of land in the California desert (Map 1). While agricultural production occurs on private land, ecological impacts can be felt beyond land ownership boundaries. For example, Imperial Valley has been heralded as one of the most productive agricultural areas in the world. In order to sustain such high productivity in an extremely arid region, the Imperial Valley diverts roughly 2.8 to 3.0 million acre-feet of surface water from the Colorado River per year, water that historically replenished aquifers and sustained natural plant and animal communities.4 Irrigation practices combined with heavy use of pesticides are responsible for the degradation of river water quality and aquatic ecosystems in the New and Alamo Rivers.5 In addition, poor water management on agricultural land can increase soil salinity and alkalinity while livestock feed and farming practices can facilitate the spread of invasive plant species.6,7

1 Bureau of Land Management. California Desert Conservation Area Plan, 1980, as amended, 1999, http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib//blm/ca/pdf/pdfs/cdd_pdfs.Par.aa6...

2 J.E. Lovich and D. Bainbridge, “Anthropogenic Degradation of the Southern California Desert Ecosystem and Prospects for Natural Recovery and Restoration,” Environmental Management 24, no. 3 (1999): 309-326.

3 D.A. Bainbridge, A Guide for Desert and Dryland Restoration, (Washington DC: Island Press, 2007).

4 University of California Cooperative Extension, Imperial County Irrigation Information, 2009, http://ceimperial.ucdavis.edu/Custom_Program275/Irrigation_Information.htm

5 V. de Vlaming, C. DiGiorgio, S. Fong, L.A. Deanovic, M. de la Paz Carpio-Obeso, J.L. Miller, M.J. Miller and N.J. Richard, “Irrigation runoff insecticide pollution of rivers in the Imperial Valley, California (USA),” Environmental Pollution 132, no. 2 (2004): 213-229.

6 D.A. Bainbridge, A Guide for Desert and Dryland Restoration, (Washington DC: Island Press, 2007).

7 M.L. Brooks, “Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Nonnative Plants in Upland Areas of the Mojave Desert,” in The Mojave Desert: Ecosystem Processes and Sustainability, ed. R.H. Webb, L.F. Fenstermaker, J.S. Heaton, D.L. Hughson, E.V. McDonald, and D.M. Miller, (Reno: The University of Nevada Press, 2009), 101-124.