Caitlin C Draft Three

From DigitalRhetoricCollaborative

(→Wayfinding) |

(→Wayfinding) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

==Modern Physical Usage== | ==Modern Physical Usage== | ||

| - | Today, the wayfinding technique in physical spaces is most commonly used for mapping and navigating in large buildings like hospitals and airports. Signs and architecture are intricately designed with the user in mind. Wayfinding airport designer Jim Harding asserts, "Ultimately, if we do our job well, wayfinding enhances the customer experience without them knowing why or how." <ref>[http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/how-you-know-where-youre-going-when-youre-in-an-airport/372537/ The Atlantic: How You Know Where You're Going When You're in an Airport]</ref> Every aspect of design is considered from signage, lighting, and color to general architecture of the space. Examples of architectural features in airports involved in wayfinding are dual carriageways, | + | Today, the wayfinding technique in physical spaces is most commonly used for mapping and navigating in large buildings like hospitals and airports. Signs and architecture are intricately designed with the user in mind. Wayfinding airport designer Jim Harding asserts, "Ultimately, if we do our job well, wayfinding enhances the customer experience without them knowing why or how." <ref>[http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/how-you-know-where-youre-going-when-youre-in-an-airport/372537/ The Atlantic: How You Know Where You're Going When You're in an Airport]</ref> Every aspect of design is considered from signage, lighting, and color to general architecture of the space. Examples of architectural features in airports involved in wayfinding are dual carriageways, escalators, entrances and exits, and check-in counters. They are designed to be easily located and provide natural signage related to their function.<ref>[http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2004900716&site=ehost-live Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.]</ref> It involves plotting predictable paths and decision points in the signage, so users can easily find their way around in unfamiliar territory. |

===Signage=== | ===Signage=== | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

[[Image:arrow.gif|thumb|right|200px|Sign with Arrow]] | [[Image:arrow.gif|thumb|right|200px|Sign with Arrow]] | ||

| - | The arrow is a tool in signage that helps to control movement and maintain stability. It guides the person in a specific direction, and the person becomes a traveler guided directly by specific procedures for movement. The arrow essentially transforms information in a certain order or direction. When the space is planned in the way a map is planned, the signs are less about representation and more about movement and directionality. The arrow, specifically, is a tool for guiding movement and behavior in an unfamiliar space. All the person needs to do is follow the arrows in order to get to a specific place.<ref>[http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2004900716&site=ehost-live Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.]</ref> | + | The arrow is a tool in signage that helps to control movement and maintain stability and is a commonly used tool in wayfinding. It guides the person in a specific direction, and the person becomes a traveler guided directly by specific procedures for movement. The arrow essentially transforms information in a certain order or direction. When the space is planned in the way a map is planned, the signs are less about representation and more about movement and directionality with the help of the arrow. The arrow, specifically, is a tool for guiding movement and behavior in an unfamiliar space. All the person needs to do is follow the arrows in order to get to a specific place.<ref>[http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2004900716&site=ehost-live Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.]</ref> |

==Modern Digital Usage== | ==Modern Digital Usage== | ||

| - | There are certain distinctions between physical wayfinding and wayfinding in digital spaces. Wayfinding in [[digital media]] is used in navigation and [[usability]] heavily connected to [[spatial affordance]] and [[procedural affordance]]. In digital spaces, there is no sense of scale or movement, no compass, no directions or clear sense of | + | There are certain distinctions between physical wayfinding and wayfinding in digital spaces. Wayfinding in [[digital media]] is used in navigation and [[usability]] heavily connected to [[spatial affordance]] and [[procedural affordance]]. In digital spaces, there is no sense of scale or movement, no compass, no directions or clear sense of moving in a certain direction.<ref> [http://webstyleguide.com/wsg3/4-interface-design/2-navigation.html Webstyle Guide to Navigation] </ref> In order to aid this, wayfinding cues are embedded into the space to keep users aware of where they are and where they might want to go. Like in physical spaces, arrows are used to direct a user to what they should click on. Home pages, [http://www.nngroup.com/articles/breadcrumb-navigation-useful/ breadcrumbs] <ref>[http://www.nngroup.com/articles/breadcrumb-navigation-useful/ Nielsen and Norman on Breadcrumbs]</ref> (reminders of visitation), and color changing links give a sense of orientation to the user. <ref>[http://webstyleguide.com/wsg3/4-interface-design/2-navigation.html Webstyle Guide to Navigation] </ref> It is particularly useful when the user is [http://www.nngroup.com/articles/deep-linking-is-good-linking/ deeplinked] <ref>[http://www.nngroup.com/articles/deep-linking-is-good-linking/ Nielsen and Norman on Deeplinking]</ref> (clicking on a link from an email or other separate system into the deeper aspects of the website's hierarchy) far into the site or use the search function instead of going through the normal progression of the site. Clear and consistent navigation is how users find information and helps them to remember which site areas they have already visited. <ref>[http://www.nngroup.com/articles/intranet-information-architecture-ia/ Nielsen and Norman Group on IA]</ref> |

===Navigation and Usability=== | ===Navigation and Usability=== | ||

[[Image:drop-down-menu.jpg|thumb|left|350px|Drop Down Menu]] | [[Image:drop-down-menu.jpg|thumb|left|350px|Drop Down Menu]] | ||

| - | Interface design is consistent | + | Interface design is consistent when each page looks similar enough that the user knows it is still the same site. Navigation is directly linked to menu bars and search bars. For maximum [[usability]] both a navigation menu or browsing option and a search bar is included. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) Breadcrumbs] <ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) Breadcrumbs Wikipedia]</ref> are reminders about what areas or pages have been previously visited or what the user's current position is in the site. Some examples are color changing links that change after they have been clicked on, tabs that change color when visited, and a home option that maintains orientation for the whole site. |

| - | Lynch's terminology has been applied to the digital space. Districts and edges (pages) are consistent with each other but still distinguishable. Nodes (interactive elements) provide choices but do not overwhelm the user. Landmarks (home page, etc) are consistently placed on each page to maintain orientation. Paths ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) breadcrumbs] <ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) Breadcrumbs Wikipedia]</ref>) are consistent, well-marked, and easily discernible for the user. Just like in a physical space, there are cues throughout the site to remind users where they are and how they can get where they need to go. | + | Lynch's terminology and distinctions of the five elements has been applied to the digital space. Districts and edges (pages) are consistent with each other but still distinguishable. Nodes (interactive elements) provide choices but do not overwhelm the user. Landmarks (home page, etc) are consistently placed on each page to maintain orientation. Paths ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) breadcrumbs] <ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breadcrumb_(navigation) Breadcrumbs Wikipedia]</ref>) are consistent, well-marked, and easily discernible for the user. Just like in a physical space, there are cues throughout the site to remind users where they are and how they can get where they need to go. |

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 15:01, 22 April 2015

Wayfinding

Wayfinding is the use of certain cues to navigate a physical or digital space. It is a termed coined by Kevin Lynch to describe environmental legibility or elements of an environment that allow successful navigation through complex spaces. [1] Originally used as a technique for navigating physical environments, it has become applicable for navigation of digital spaces and web design.

Contents |

History

Wayfinding did not develop until the early 20th century when the term was coined by Kevin Lynch in The Image of the City in which he recognized the importance of an environmental image in wayfinding or navigational tasks.[2] He divided the elements of a city into five distinct groups: paths (streets, bus lines, etc), edges (physical barriers such as walls or rivers), districts (places with distinct identities such as Wall Street or the Empire State Building), nodes (major intersections or meeting places), and landmarks (visible structure that can be used to assess orientation over long distances).[3] Architects, urban planners, landscape architects, environmental graphic designers, and behavioral and cognitive psychologists have all contributed to the study of wayfinding.[4]

Modern Physical Usage

Today, the wayfinding technique in physical spaces is most commonly used for mapping and navigating in large buildings like hospitals and airports. Signs and architecture are intricately designed with the user in mind. Wayfinding airport designer Jim Harding asserts, "Ultimately, if we do our job well, wayfinding enhances the customer experience without them knowing why or how." [5] Every aspect of design is considered from signage, lighting, and color to general architecture of the space. Examples of architectural features in airports involved in wayfinding are dual carriageways, escalators, entrances and exits, and check-in counters. They are designed to be easily located and provide natural signage related to their function.[6] It involves plotting predictable paths and decision points in the signage, so users can easily find their way around in unfamiliar territory.

Signage

Signage is a spatial mode of interactivity with the user that transforms unfamiliar terrains with the help of familiar authority such as easily recognizable symbols and titles. Well executed wayfinding signage will allow the user to form a mental map of the space that can be used to inform decisions and action plans. It is vital that all signage can be easily understood by a wide variety of users and can be seen from an acceptable distance.[7]

The Arrow

The arrow is a tool in signage that helps to control movement and maintain stability and is a commonly used tool in wayfinding. It guides the person in a specific direction, and the person becomes a traveler guided directly by specific procedures for movement. The arrow essentially transforms information in a certain order or direction. When the space is planned in the way a map is planned, the signs are less about representation and more about movement and directionality with the help of the arrow. The arrow, specifically, is a tool for guiding movement and behavior in an unfamiliar space. All the person needs to do is follow the arrows in order to get to a specific place.[8]

Modern Digital Usage

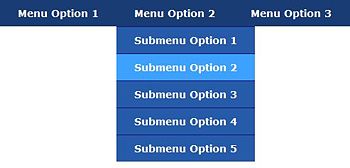

There are certain distinctions between physical wayfinding and wayfinding in digital spaces. Wayfinding in digital media is used in navigation and usability heavily connected to spatial affordance and procedural affordance. In digital spaces, there is no sense of scale or movement, no compass, no directions or clear sense of moving in a certain direction.[9] In order to aid this, wayfinding cues are embedded into the space to keep users aware of where they are and where they might want to go. Like in physical spaces, arrows are used to direct a user to what they should click on. Home pages, breadcrumbs [10] (reminders of visitation), and color changing links give a sense of orientation to the user. [11] It is particularly useful when the user is deeplinked [12] (clicking on a link from an email or other separate system into the deeper aspects of the website's hierarchy) far into the site or use the search function instead of going through the normal progression of the site. Clear and consistent navigation is how users find information and helps them to remember which site areas they have already visited. [13]

Navigation and Usability

Interface design is consistent when each page looks similar enough that the user knows it is still the same site. Navigation is directly linked to menu bars and search bars. For maximum usability both a navigation menu or browsing option and a search bar is included. Breadcrumbs [14] are reminders about what areas or pages have been previously visited or what the user's current position is in the site. Some examples are color changing links that change after they have been clicked on, tabs that change color when visited, and a home option that maintains orientation for the whole site.

Lynch's terminology and distinctions of the five elements has been applied to the digital space. Districts and edges (pages) are consistent with each other but still distinguishable. Nodes (interactive elements) provide choices but do not overwhelm the user. Landmarks (home page, etc) are consistently placed on each page to maintain orientation. Paths (breadcrumbs [15]) are consistent, well-marked, and easily discernible for the user. Just like in a physical space, there are cues throughout the site to remind users where they are and how they can get where they need to go.

References

- ↑ Webstyle Guide to Navigation

- ↑ International Digital Media and Arts Association on Wayfinding

- ↑ Webstyle Guide to Navigation

- ↑ International Digital Media and Arts Association on Wayfinding

- ↑ The Atlantic: How You Know Where You're Going When You're in an Airport

- ↑ Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Fuller, Gillian. "The Arrow--Directional Semiotics: Wayfinding In Transit." Social Semiotics 12.3 (2002): 231. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Webstyle Guide to Navigation

- ↑ Nielsen and Norman on Breadcrumbs

- ↑ Webstyle Guide to Navigation

- ↑ Nielsen and Norman on Deeplinking

- ↑ Nielsen and Norman Group on IA

- ↑ Breadcrumbs Wikipedia

- ↑ Breadcrumbs Wikipedia