Michelle draft two

From DigitalRhetoricCollaborative

(New page: =Spatial Affordance= The <b>Spatial Affordance</b> in multimedia is a concept that refers to the ability of a digital medium to represent space, as well as encourage navigation throug...) |

|||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| - | + | The concept of [[affordances]] was first introduced by James Gibson (1979)<ref>Gibson, James J. (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception</ref> referring to the “action possibilities” of an object. For example, throwing is an action possibility of a ball the size of one’s hand. This concept was then expanded by Donald Norman (1988)<ref>Norman, Donald A. (1988): The Design of Everyday Things. New York, Doubleday</ref> to include the “perceived and actual properties” of an entity. Affordances then also referred to the inherent quality of an object that a user is able to perceive. Because an affordance is also based on user perception, the possibilities of an object are dependent on the user.<ref>http://mystsphdquest.blogspot.com/2012/11/spatial-affordances.html</ref><ref>https://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/affordances.html</ref> | |

| + | |||

| - | |||

Janet Murray, one of the forefront authors on affordances, has since defined affordances in the context of digital text. She describes it as “A concept used in the field of human computer interaction to describe the functional properties of objects or environments – the properties that allow particular uses.<ref>Murray, Janet H. Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2012.</ref> For example, a blackboard affords writing and erasing, a low, flat, supported surface 30 inches square affords sitting.” | Janet Murray, one of the forefront authors on affordances, has since defined affordances in the context of digital text. She describes it as “A concept used in the field of human computer interaction to describe the functional properties of objects or environments – the properties that allow particular uses.<ref>Murray, Janet H. Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2012.</ref> For example, a blackboard affords writing and erasing, a low, flat, supported surface 30 inches square affords sitting.” | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

[[Image:Inventing_the_medium_cover.jpg|thumb|left|alt=the cover of Inventing the Medium by Janet Murray.|The cover of Janet Murray's <i>Inventing the Medium</i>.]] | [[Image:Inventing_the_medium_cover.jpg|thumb|left|alt=the cover of Inventing the Medium by Janet Murray.|The cover of Janet Murray's <i>Inventing the Medium</i>.]] | ||

| - | Janet Murray is the author of several texts concerning affordances in digital media. Notable books of her's include <i>[http://inventingthemedium.com/ Inventing the Medium]</i>, which defines the spatial affordance as such: | + | |

| - | "With the encyclopedic, participatory, and procedural properties, | + | [[Janet Murray]] is the author of several texts concerning affordances in digital media. Notable books of her's include <i>[http://inventingthemedium.com/ Inventing the Medium]</i>, which defines the spatial affordance as such: |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | "With the encyclopedic, participatory, and procedural properties, (the spatial affordance is) one of the four defining representational affordances of the digital medium. Digital environments can represent space using all the strategies of traditional media, such as maps, images, video tracking, and three-dimensional models. Unlike older media, however, and similarly to the experiential world and the designed spaces of landscapers, urban planners, and architects, digital media artifacts can be navigated. This affordance is not a function of visual representation, since it can be produced in text adventure games like Zork and Adventure, which created navigable spaces without any images. It is by-product of the procedural and participatory affordances, of setting up rules of interaction that have the consistency of navigating a fixed landscape, and of the innate human propensity to make sense of the world through spatial metaphors: we are predisposed to spatialized our experience, turning the appearance of text on our screen into the experience of “visiting’ web sites. Navigable space is created by clearly distinguishing one place from another and creating consistent interaction patterns that support movement between spaces. When encyclopedically large and detailed informational spaces or virtual worlds are well organized with clear boundaries, consistent navigation, and encyclopedic details that reward exploration they create the experience of immersion." <ref>http://inventingthemedium.com/glossary/#spatial</ref> | ||

| + | |||

According to Murray's definition, spatial affordances do not represent real space, but instead act as an abstraction that may be used to fulfill a certain function or provide a certain piece of information. All of the spatial affordances working together in a text create easy user navigation of the text. | According to Murray's definition, spatial affordances do not represent real space, but instead act as an abstraction that may be used to fulfill a certain function or provide a certain piece of information. All of the spatial affordances working together in a text create easy user navigation of the text. | ||

| Line 56: | Line 60: | ||

| - | + | ==External Links== | |

| + | [http://inventingthemedium.com/ Inventing the Medium] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

Revision as of 14:05, 22 April 2015

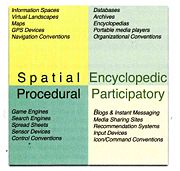

Spatial Affordance

The Spatial Affordance in multimedia is a concept that refers to the ability of a digital medium to represent space, as well as encourage navigation through that space via organization and spatial metaphors. Affordances, including the spatial affordance, as well as the procedural affordance, participatory affordance, and the encyclopedic affordance]], suggest how an entity could or should be used.[1] Spatial affordances employ a hierarchy of labels, where each space possesses its own label and function. When spatial affordances are appropriately used, the labels of each space will make obvious the space’s function.

The spatial affordance in digital media is understood today based on based on work in fields such as wayfinding, mapping, and curation, which primarily consider the spatial affordances of physical entities. Specifically, articles discussing the ability of wayfinding and mapping to encourage navigation have influenced how space is utilized in digital media.

Contents |

Background

The concept of affordances was first introduced by James Gibson (1979)[2] referring to the “action possibilities” of an object. For example, throwing is an action possibility of a ball the size of one’s hand. This concept was then expanded by Donald Norman (1988)[3] to include the “perceived and actual properties” of an entity. Affordances then also referred to the inherent quality of an object that a user is able to perceive. Because an affordance is also based on user perception, the possibilities of an object are dependent on the user.[4][5]

Janet Murray, one of the forefront authors on affordances, has since defined affordances in the context of digital text. She describes it as “A concept used in the field of human computer interaction to describe the functional properties of objects or environments – the properties that allow particular uses.[6] For example, a blackboard affords writing and erasing, a low, flat, supported surface 30 inches square affords sitting.” Murray asserts that there are four affordances that are useful for representation within the digital realm: procedural, participatory, encyclopedic, and spatial. [7]

Janet Murray's Spatial Affordance

Janet Murray is the author of several texts concerning affordances in digital media. Notable books of her's include Inventing the Medium, which defines the spatial affordance as such:

"With the encyclopedic, participatory, and procedural properties, (the spatial affordance is) one of the four defining representational affordances of the digital medium. Digital environments can represent space using all the strategies of traditional media, such as maps, images, video tracking, and three-dimensional models. Unlike older media, however, and similarly to the experiential world and the designed spaces of landscapers, urban planners, and architects, digital media artifacts can be navigated. This affordance is not a function of visual representation, since it can be produced in text adventure games like Zork and Adventure, which created navigable spaces without any images. It is by-product of the procedural and participatory affordances, of setting up rules of interaction that have the consistency of navigating a fixed landscape, and of the innate human propensity to make sense of the world through spatial metaphors: we are predisposed to spatialized our experience, turning the appearance of text on our screen into the experience of “visiting’ web sites. Navigable space is created by clearly distinguishing one place from another and creating consistent interaction patterns that support movement between spaces. When encyclopedically large and detailed informational spaces or virtual worlds are well organized with clear boundaries, consistent navigation, and encyclopedic details that reward exploration they create the experience of immersion." [8]

According to Murray's definition, spatial affordances do not represent real space, but instead act as an abstraction that may be used to fulfill a certain function or provide a certain piece of information. All of the spatial affordances working together in a text create easy user navigation of the text.

Spatial Affordance Concepts

Wayfinding

Before digital media, there were (and still are) processes that focused on how to best use a space to send messages and provide cues to those who interacted with that space. This process is called wayfinding ((cite to wayfinding DRC WIKI PAGE)). Wayfinding uses lighting, color, architecture, etc. to help users navigate a space, and when best done, users should not notice that they are subject to it.

Wayfinding, like working with the spatial affordances of a digital text, considers how each space affects the surrounding space, and attempts to “establish a sense of place” for users so that the entire space is easily navigated.[9] For example, appropriate use of wayfinding in an airport includes the use of organized and clearly labeled signs and obvious symbols for food and restroom stations. Getting lost or made perplexed by an airport sign disrupts the space’s sense of navigation and points to poor wayfinding and poor use of the spatial affordance. [10]

Mapping

Mapping provides another example of how to think about the use of spatial affordances. Maps have “postings,” such as streets, churches, neighborhoods, and cities. These postings are organized in a hierarchal fashion that convey the level of authority each posting has in relation to one another. Like in media, in mapping each posting related to another implies something about each individual space, and these relationships encourage use of the overall space. Additionally, maps use symbols, such as a cross for a church or a book for a school, that are meant to act as spatial representations that allow for the seamless navigation of the map.[11]

Curation

Museum design via curation also is based on utilizing spatial affordances. Research by Jean Wineman and John Peponis from the Georgia Institute of Technology suggests that human behavioral patterns are directly linked to spatial elements that encourage access and visibility. Wineman & Peponis (2010) stress that the use of the space and the physical structure of a museum exhibit entirely effects a visitor’s impression, learning, and interaction with the exhibit[12], just as the use of the spatial affordance in media affects a user’s ability to navigate a digital text.

The Spatial Affordance Related to Other Affordances

Examples of Spatial Affordance Use

Within any text, affordances of space are used, but there are some digital texts that have been considered to best use the spatial affordance. Example texts include:

- The winner of the 2013 Webby Awards for Best Navigation/Structure: Clouds over Cuba[13]

- The winner of the 2014 Webby Awards for Best Navigation/Structure: Behance.net[14]

- The "People's Choice" Award Winner for Best Navigation/Structure: The Last Hunt[15]

External Links

References

- ↑ https://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/affordances.html

- ↑ Gibson, James J. (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception

- ↑ Norman, Donald A. (1988): The Design of Everyday Things. New York, Doubleday

- ↑ http://mystsphdquest.blogspot.com/2012/11/spatial-affordances.html

- ↑ https://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/affordances.html

- ↑ Murray, Janet H. Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2012.

- ↑ Murray, Janet H. Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2012.

- ↑ http://inventingthemedium.com/glossary/#spatial

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/how-you-know-where-youre-going-when-youre-in-an-airport/372537/

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/how-you-know-where-youre-going-when-youre-in-an-airport/372537/

- ↑ http://makingmaps.owu.edu/this_is_not_krygier_wood.pdf

- ↑ Wineman, Jean D., and John Peponis. "Constructing Spatial Meaning: Spatial Affordances In Museum Design." Environment And Behavior 42.1 (2010): 86-109. ERIC. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ i. http://www.webbyawards.com/winners/2013/web/general-website/associations/

- ↑ http://www.webbyawards.com/winners/2014/web/website-features-and-design/best-navigationstructure/

- ↑ http://pv.webbyawards.com/2015/web/website-features-and-design/best-navigationstructure