Vannevar Bush Rough Draft

From DigitalRhetoricCollaborative

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| - | *[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c539cK58ees|Video demonstrating the ideas behind the Memex system] | + | *[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c539cK58ees| Video demonstrating the ideas behind the Memex system] |

*[http://dl.tufts.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=vannevar+bush&search_field=all_fields Pictures of Vannevar Bush from the Tufts Digital Library] | *[http://dl.tufts.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=vannevar+bush&search_field=all_fields Pictures of Vannevar Bush from the Tufts Digital Library] | ||

*[http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/bush-vannevar.pdf National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir] | *[http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/bush-vannevar.pdf National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir] | ||

Current revision

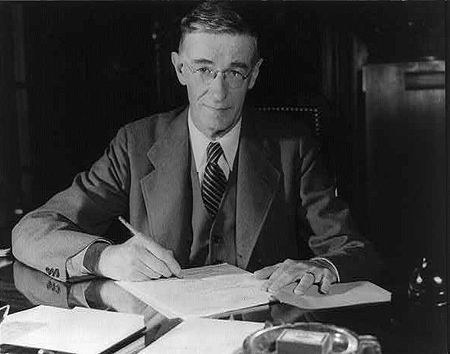

[edit] Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush (March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer and inventor known for his visionary Atlantic Monthly article titled As We May Think which introduced his hypothetical “memex,” a microfilm device akin to modern hypertext. Published in 1945, the article described the memex as a "device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.”[2] Bush envisioned his device as a utilitarian work desk, replete with a screen and a system of buttons and levers that manipulated its many functions. However, instead of using traditional storage patterns based around indexes and structural hierarchies, the memex would organize information based on associative links similar to the way the human brain processes, stores, and remembers information. It would have the ability to link associated pieces of information together and, in the process, generate more linkages, creating an “associative trail” of information and memory at the tip of one’s fingers.[3] Since it functionally operated in ways similar to human memory, Bush viewed his device as a mechanical appendage to the human mind that could “give man access to and command the inherited knowledge of the ages.”[4]

Contents |

[edit] Wartime Administrative Career

Prior to writing As We May Think in 1945, Bush acted as a founding member of Raytheon, one of America’s leading defense contractors and electronics corporations, while also serving as a pioneer in the field of analog computers. At the start of World War II, Bush recognized a growing need for scientific research directed toward the war effort. Using Fredric Delano, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s trusted uncle, as an intermediary, Bush proposed the creation of a new federal department that would “correlate and support scientific research on mechanisms and devices of warfare.” [5] Roosevelt approved and established the National Defense Research Committee, naming Bush the department’s chairman. However, the NDRC was funded by a presidential emergency fund, exposing it to perilous financial restraints. [6] In May of 1941, Roosevelt established the congressionaly funded and less legally limited Office of Scientific Research and Development, an organization that subsumed Bush’s NDRC. Roosevelt appointed Bush director of the OSRD, giving him the authority to begin developing small batches of weapons. While serving as the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Bush advocated for and oversaw America’s burgeoning atomic program, a program eventually christened the Manhattan Project and credited with the creation of the atomic bomb.

[edit] Genesis of As We May Think

In World War II’s immediate aftermath, Bush began to set his sights on the future. Looking to capitalize on the technological fervor of post-war America, he advocated for continuing the convergence of federal defense funding and private, civilian research. Military might, in Bush’s mind, could no longer be achieved without scientific innovation. But even beyond the sphere of American militarism, Bush envisioned a world where increased technological and mechanical capabilities would push the limits of human cognition and ability. In the early lines of the article he claims, “The world has arrived at an age of cheap complex devices of great reliability; and something is bound to come of it.”[7] But Bush does not simply use the article to advocate for an increase in research and innovation. In fact, he takes a fundamental step back. The article serves as a petition to the researchers of the world to find new ways to catalog, share, decipher, and transmit much of the technological advancements made during the war effort. He writes:

So much for the manipulation of ideas and their insertion into the record. Thus far we seem to be worse off than before—for we can enormously extend the record; yet even in its present bulk we can hardly consult it. This is a much larger matter than merely the extraction of data for the purposes of scientific research; it involves the entire process by which man profits by his inheritance of acquired knowledge. The prime action of use is selection, and here we are halting indeed. There may be millions of fine thoughts, and the account of the experience on which they are based, all encased within stone walls of acceptable architectural form; but if the scholar can get at only one a week by diligent search, his syntheses are not likely to keep up with the current scene.[8]

He believed that the nascent technology of digital and analog computing, along with the human-machine interaction in general, were the most important factors in the dissemination information."[9] The automation of thought would only aid and expand the powers of human memory and thus, further enable scientific advancement. Though noted most often for its description of the “memex,” many of the technologies described by Bush are perceived as forerunners of modern innovations like hypertext, the World Wide Web, and speech recognition.

[edit] From Memex to Hypertext

While different, Bush’s “memex” is seen as a hypothetical precursor to modern hypertext. In As We May Think, he claims that the “essential feature of the memex” is its ability to intuitively index records based on association rather than on numerical, alphabetical, or subclass hierarchy.[10]Bush’s memex held the power to mechanically connect a sequence of related documents he referred to as a “trail” that could be stored for later use. Bush, however, was theoretically operating in a world void of modern computer storage, meaning that his user was bound by the storage capacity of the document “trail.” The user was also only able to maneuver to documents within a given trail or at the intersection of two trails. Modern computers, with their vast storage capacities, eliminate these restrictions and make possible a much more complex structure of associated information that can branch in a number of different directions.[11] Thomas Nelson, the man who coined the terms “hypertext” and “hypermedia,” recognized the potential for such a complex structure and began working on the Project Xanadu, a Brown University research project that sought digitally link together various texts. In 1967, under the leadership of Andries Van Dam, Brown University completed the Hypertext Editing System, the world first hypertext system. A year later,Douglas Englebart gave “The Mother of All Demos” demonstration where he introduced the NLS (oN-Line System)project, a system with several hypertext features, which introduced the basic principles of interactive computing to the general public.[12]

[edit] External Links

- Video demonstrating the ideas behind the Memex system

- Pictures of Vannevar Bush from the Tufts Digital Library

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

[edit] References

- ↑ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vannevar_Bush_portrait.jpg

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

- ↑ Zachary, G. Pascal. Endless frontier : Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American Century. n.p.: New York : Free Press, c1997., 1997, 262.

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

- ↑ Zachary, G. Pascal. Endless frontier : Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American Century. n.p.: New York : Free Press, c1997., 1997,112.

- ↑ Zachary, G. Pascal. Endless frontier : Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American Century. n.p.: New York : Free Press, c1997.,1997,129.

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

- ↑ Zachary, G. Pascal. Endless frontier : Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American Century. n.p.: New York : Free Press, c1997., 1997,262.

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

- ↑ Bush, Vannevar, James M. Nyce, and Paul Kahn. From Memex to hypertext : Vannevar Bush and the mind's machine. n.p.: Boston : Academic Press, c1991.,1991

- ↑ Nielsen, Jakob. Hypertext and hypermedia. n.p.: Boston : Academic Press, c1990., 1990,34.