Stakeholder Perceptions and Study Findings

We explored how community attitudes toward solar development relate to the ecological and socioeconomic impacts predicted in other segments of our study. We found that, in some cases, public perception correctly predicted with what we determined to be a likely outcome, and in others, public perception was misguided and should be addressed through additional community outreach tactics utilizing those channels preferred by community stakeholders, as discussed later in Information Gaps and Sources. Table 1 summarizes these findings.

| Impact Category | Public Perception | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Technological | ||

| Energy Availability | Likely and Valuable | Likely but Value Uncertain |

| Water Quantity | Most Concerned | Cause for Concern |

| Ecological | ||

| Water Quality | Most Concerned | Cause for Concern |

| Habitat Damage | Somewhat Likely | Probable |

| Air Quality | Not Likely | Possible |

| Spatial | ||

| Viewshed | Less Concerned | Probable |

| Socioeconomic | ||

| Construction Jobs | Likely and Valuable | Not Likely |

| Operation Jobs | Likely and Valuable | Not Likely |

| Town Budget | Likely and Valuable | Not Likely |

Technological

We asked respondents how likely they thought “increased energy availability/reliability for California residents” would be if a utility-scale solar facility were constructed near their town. Based on the survey responses received, greater availability of energy was seen as both highly likely (4.10 on a 5 point scale) and highly valuable (4.31 on a 5 point scale). In fact, energy was seen as the most valuable of all the potential positive outcomes listed in the survey. This stakeholder perception is aligned with probable outcomes, since the development of these facilities will have some impact on the availability of energy in California. Even if only 13 out of the 54 projects currently being reviewed by the California Energy Commission (CEC) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) were developed, they would provide an additional 13 million megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity annually, enough to power more than 1.1 million U.S. homes, given that the average U.S. home uses 11,040 kWh per year.1 Electricity from solar facilities will then be fed into the grid and sent wherever there is demand.

However, respondents interpreted the question as an increase in availability of electricity to their community, or a lower cost of electricity, which is unlikely. This potential misconception demonstrates the need for additional education at the public meetings regarding how and where the new electricity will be utilized.

Ecological

We also gauged the degree of concern over “decreased quantity or quality of water in streams, springs, and wells,” an issue which respondents cited as their greatest concern (3.20 on a 5 point scale). It was also the issue that the most respondents — 14 percent — expressed uncertainty about the likelihood of happening. Given the importance of water in this region as well as respondents’ uncertainty about the impacts of these facilities, it is not surprising that respondents also indicated that they would find more information about water usage of these facilities useful (4.36 on a 5 point scale).

Our analysis has indicated that the communities’ concerns as well as their uncertainty about water are reasonable. Utility-scale solar energy facilities, similar to other industrial operations, have substantial water needs. In an effort to combat the potentially irreversible draw down of desert aquifers, the CEC has issued guidance to developers that dry cooled systems should be utilized and that wet cooled systems are extremely unlikely to be allowed by the agency. It would be useful to communicate this measure to desert residents. However, all technology types will require some water for panel or mirror washing, though water sources vary on a project-by-project basis. A compounding factor to this issue is the complexity of aquifers and hydrologic systems in our study area, making predictions about the impacts to regional water levels difficult. Additionally, site engineering and surface water diversions could alter water infiltration and flow to natural streams and springs, while water quality could be compromised if chemicals used for vegetation control end up as runoff into the surrounding ecosystem. Again, given the results of our survey, we believe it would be in the BLM’s best interest to develop information campaigns around water use estimates and conservation measures.

At 3.04 out of 5, “Decreased Wildlife and Plant Habitat” was ranked second on the list of concerns for our respondents. However, they scored the likelihood of this happening lower, at 2.82. With a variance of 2.21, it was also an issue that residents disagreed about, more so relative to other issues. These scores suggest that, while desert residents are unsure about whether habitat loss or disturbance will occur as a result of solar development, local communities should examine these potential consequences in more detail. As our ecological impact analyses suggest, the public may currently be underestimating the potential for habitat loss following facility construction. Perimeter fencing will effectively eliminate habitat for species unable to penetrate the barrier, while grading and vegetation removal may destroy habitat within the site for birds or smaller species that still may be able to access the area despite fencing. Given the level of concern regarding these impacts, our survey analysis suggests education about the likelihood of potential impacts to wildlife and plant habitat may be of value to local residents.

The survey results also indicate that respondents believe decreased air quality is a relatively unlikely impact of solar development (1.89 on a 5 point scale). This public perception, however, may represent an underestimation of this potential, or a lack of understanding about how air quality may be affected by facility construction in our study area. The site engineering associated with development, especially grading and vegetation removal, has a high potential for dust emission. These processes will disturb soil structure and stability, releasing dust into the atmosphere. Large dust emissions could also occur if dust-sequestering biological soil crusts are on the facility site and are crushed during construction. Additionally, activities that result in drier soil surfaces may lead to increased dust; this may include vegetation removal, soil compaction that reduces water infiltration, and groundwater pumping that diminishes streams, springs and seeps. Given the high potential for dust emission as a result of solar development, air quality may be reduced for residents living in close proximity to, or downwind of a facility — especially during the construction phase. As discussed earlier, dust can travel great distances, so impacts to air quality should be considered for residents in a broad geographic area.

Spatial

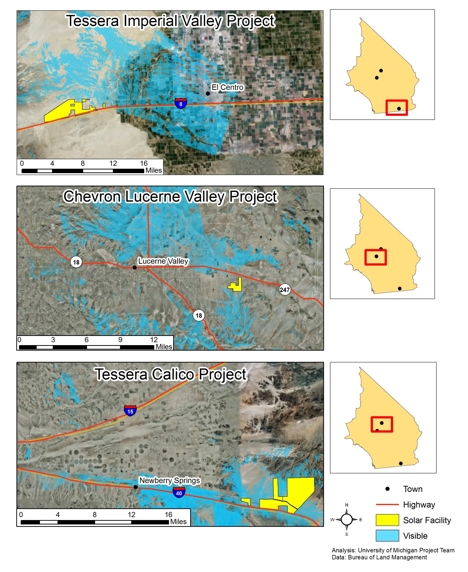

The impact to the viewshed was the fifth most cited negative consequence of solar development in our open-ended response keyword analysis. However, respondents rated “decreased quality of vistas from your town” as the outcome they were least concerned about with an average rating of 2.5 out of 5. This discrepancy might be best explained by the nature of the open-ended responses; half of those who cited viewshed impact suggested that it would have an impact on the view but that it was not something that might bother them. A related sentiment observed in the open-response questions was that of the desert being “barren” or “otherwise useless.” That said, the variance of the closed-ended response was 2.27 out of 5, indicating that there is quite a bit of disagreement between respondents, where responses were grouped at extremes. While concern over an altered viewshed varies, a closer look at the likely visual impacts indicates that residents are likely to be affected by the proposed facilities, both in many parts of the communities and along primary highways leading in and out of town. This being the case, it might be useful for the BLM to mock up what the visual impact will be from ground level to allow residents to either temper their concern or reevaluate their indifference. We have created an example of such a map (Map 1).

Socioeconomic

Respondents ranked increased employment opportunities during facility construction and operation as both highly likely and quite valuable. Unfortunately, this optimistic outlook may prove unfounded. Although facility construction will create hundreds of temporary jobs, the labor pool in the California desert includes thousands of individuals; residents will face stiff competition for these positions. Once in operation, each facility will require relatively few full-time employees: of 14 proposed facilities reviewed in this study, 10 expected to create fewer than 100 permanent positions each, whereas the other four could create more. While a handful of respondents indicated skepticism about job creation for their communities, many more expressed hope.

Respondents also believe that it is likely that solar development in the California desert will have a positive impact on local municipal budgets. However, facilities sited on federal land will have few direct local fiscal impacts; all lease payments will go to the U.S. Treasury. Given that federal land is property tax exempt, facilities on public land will probably not result in increased local property tax revenue, unless payments in lieu of taxes are made. Facilities sited on both public and private land may have local fiscal benefits; for example, these private landowners will benefit directly from lease payments. Furthermore, infrastructure on private land that is unrelated to energy production, such as office buildings, may be assessed property tax, thereby benefiting the local unit of government. Some of these misunderstandings are related to a lack of understanding of the technology and what it does, an issue also explored in our survey.

1 U.S. Energy Information Administration. Frequently Asked Questions – Electricity. http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/ask/electricity_faqs.asp.